“Bicycles are simple products, vehicles with simple intelligent structures. This is the attraction for me and why I want to design and build them with stories.”

If you’re going to visit a bicycle frame builder, it only seems fit to visit them on two wheels. The question is, can my two legs turn my two wheels the 380 km from Ishikawa to Wakayama, the home of KUALIS Cycles? This is my human powered journey to visit Yoshi Nishikawa and listen to the stories that go into each custom bicycle frame he designs.

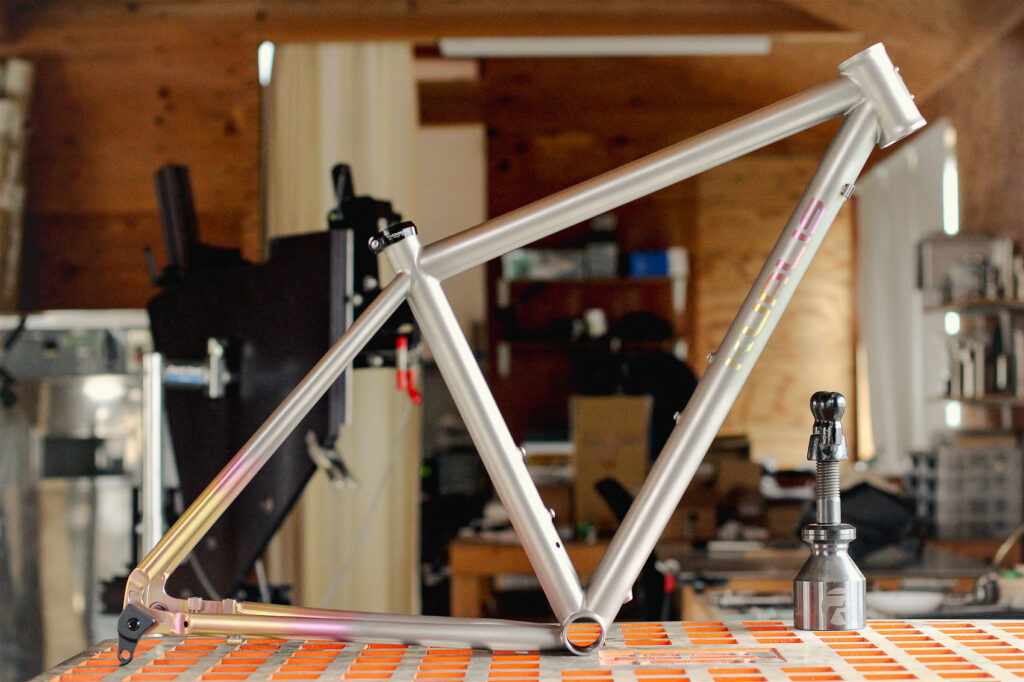

The first thing Yoshi does is make us a cup of KUALIS dark roast coffee, before jumping into technical talk. The Titanium frame making process is more complex than steel. Off the shelf titanium butted tubing is more complex than straight tubing and custom made butted tubing more complex still. Yoshi enjoys using all types of tubing, each having their own particular look and feel, all good for different reasons. Nonetheless, his unique skill lies in making titanium frames with custom made butted tubing. What is butted tubing? Butted tube design means carefully making different thickness sections along the length of a bicycle frame tube. To be precise, along the top tube, down tube and seat tube. Different types of butting in different combinations create different ride feels. He is the only frame builder in Japan making custom titanium frames this way and his frames are beautiful not only to look at, but to ride. However, the real beauty lies in the invisible design. The invisible is where the design magic happens and it is this invisible design that excites Yoshi the most.

A winter has passed since I’d ridden my bike and years since I’d ridden so far. Friends came together to help me on my way; A stock of The Small Twist Trailfoods ‘The BAG’ from Yuka & Kosuke Yamato, A KS Ultralight Daypack from Laurent Barikosky and a tenugui from Keigo Kamide. The going was easy until I turned southwest into the coastal headwinds. As I cycled I repeated the mantra “you are not allowed to order a new bike… you are not allowed to order a new bike”.

Yoshi has put in the hours, studying architecture at Tokyo Gakugei University, before realising that he not only wanted to design, but also to make. He’s modest when it comes to why he wanted to make bicycle frames, simply saying that he wanted to make something smaller than a house and it was the cycling culture that attracted him. Bicycles are simple intelligent machines taking mastery of material and technique to build. Add to that a background in architecture and you have a mastery of geometry and structural integrity too. This is the invisible magic I mentioned. Yoshi’s frames are stunningly designed in both the visible and invisible, following a unique story he creates for each customer.

Starting his apprenticeship at Level Cycles in Japan, moving to Seven Cycles in Boston a few years later. It was here where he mastered the technique of TIG welding and the use of titanium as a frame material. After more than 11 years of frame design and building experience, it was time for Yoshi to breakaway and start KUALIS Cycles on his own.

Leaving the wonderful Ayukawaenchi Camping Ground at 6am, I pedalled on through the Fukui headwind, now with rain for good measure. Sheltering under the roof of a rundown rest stop I peered down the misty coast towards what I thought might be today’s destination; Tsuruga.

Orders were coming in and life in America was good. However, most of the orders were for customers in Japan, so Yoshi’s next logical step was to move back home. Before leaving the US he designed a house and workshop to be built on an empty piece of family land. Once nothing but fields, now suburban Wakayama, where his parents still live in their original house. Yoshi points out his father’s drawing room, a small building in the garden between his parents house and his frame building workshop. Side by side, life in Wakayama is also good. Instead of riding the North Shore or Charle River in Boston, Yoshi now rides his hand built bike along the pathways of Kinokawa (Kino River).

“Closed? Is it really closed?” I pleaded. “I can carry my bike if I have to?”. 10km up the nonexistent gravel road intended to lead me over the mountains, I was turned around by a team of workmen. 10km backtracking later, I’m sneaking onto the train praying the driver doesn’t notice my nonexistent bike bag. When I casually walked my bike out of the station three stops later, it felt like I was in another country. Energised, I followed the Biwaichi Cycling Route, finding lunch at the Shared Kitchen Hakko, and free camping at Omi-Maiko Nakahama Beach.

Yoshi is busy, admitting to working almost everyday. Just then his office telephone rings and Yoshi slips away for a moment before returning and saying “That’s another order” barely changing his calm expression. This time next year that customer will receive their new titanium bike, making only fifty frames a year for customers all over the world. I asked Yoshi how he felt having so many back-orders. For some people back-orders offer a sense of security, whereas for others, it’s a loss of freedom. Yoshi is simply happy to be busy doing what he enjoys. If he feels stressed he goes fishing to reset his mind, occasionally to his surprise catching a fish. “It is sometimes stressful, but it’s good stress.” We discuss the type of stress that designers often feel from wanting things —our craft— to be perfect. Not the ‘get me outta here’ type of stress from doing something you hate. We laugh in the happy understanding that we’re not alone and the odd sleepless night comes with the territory.

Yesterday ended with a swim in the lake; today I’m sitting in Hoteiyu’s 110ºC+ sauna. Extending the cold baths in the hope my muscles might recover. Hours before traversing Otsu, Yamashina and the dreaded Kumiyama Highway junction on my way to the famous Kōzuya Bridge. Beyond that joining the Keinawa Cycling Road from Kyoto to Wakayama, my route for the next couple of days.

As we explored his workshop —one frame being checked before welding, another resting after welding— I asked Yoshi about design inspiration and we compared stories of the 90’s cycle courier cultures in Tokyo and London. How their bikes were customised in the name of speed, style and anti-theft, creating a fascinating design aesthetic. Yoshi and I are about the same age and the same height so I instantly took him up on the offer to try his own KUALIS bike. A titanium hardtail mountain bike frame (straight tubing not butted) with a rigid carbon fork and Chris King components. “This is my daily bike; I use it to go fishing,” he explains. KUALIS is from the old Latin “Qualis” meaning “Quality”. Yoshi replaced the ‘Q’ with a ‘K’ to create the original name KUALIS (quality) and the quality of Yoshi’s frames was evident. As I lifted his bike, it almost floated away and it floated more as I rode it around the neighbourhood whispering “you are not allowed to order a new bike…”.

Quietly leaving the other guests sleeping in their bunk beds. I rode out of Nara with a smile on my face. Eating up the kilometres on the smooth bike path felt good, but I missed the more interesting back roads. Leaving the sun-burning plains of Nara behind, I entered the hillside orchards of the Yoshino River. Next stop Gojo.

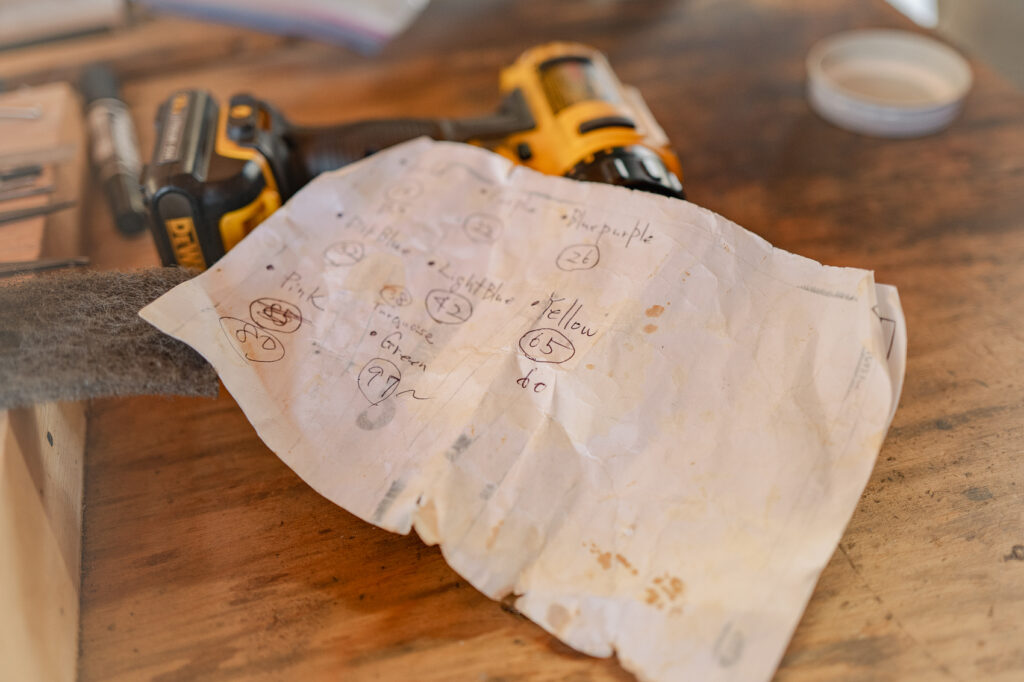

It’s fair to say, Yoshi loves the process of building bikes, especially translating each customer’s order into a story. A story of rider + style of riding + surface conditions. Then using his intuition and a mastery of the visible and invisible design, Yoshi confidently transforms each story into a frame. Each customer’s story is different therefore each frame design is unique. The frame tubes are made in-house, cut, butted or bent on a series of customised tools and jigs. More complex parts such as disc-brake mounts and dropouts are made by specialists following Yoshi’s designs. Some parts milled, others 3D printed —I didn’t know you could 3D print titanium, but you can and it’s beautiful. Beautiful too are the frame finishes, ceramic bead blasted or brushed, painted or may particular favourite; anodised. While Yoshi showed me his anodising technique I started to fantasise about what finish I would choose for my own Kualis frame.

Yamada Ryokan’s owners waved goodbye behind me, the cycling path stretching out in front of me and the sun beared down on me. I was officially sunburnt, but the omnipresent headwind kept me cool. A few hours later I crept wearily into Wakayama and the wonderful Guesthouse RICO. Sauna, beer, then I slept the sleep of accomplishment.

One of the first things that struck me about Yoshi was his unpretentious nature: perhaps his greatest quality. Like his frames he doesn’t scream for attention, but quietly exudes great confidence in the knowledge that the design, function and construction is of the highest quality. I understand now that KUALIS meaning quality is the perfect name for Yoshi’s frames.

It was time for Yoshi to get back to work making bikes. Just two questions left; What does success mean to him? & Why am I always riding into a headwind? Yoshi had answers for both. “Climbing over each small goal is a success” and “at this time of year, winds blow north as the season changes from winter to summer.” I should’ve cycled home north, not south to Wakayama!

I opened the car window to say my final goodbyes, still repeating the mantra; “you are not allowed to order…” Yoshi interrupted my thought “By the way… I’ll give you a discount if you ever wanted to order… a new bike.!”

and so it goes.

Find Yoshi and Kualiscycles at:

Kualiscycles.com

Instagram

Facebook

Find James Gibson and more stories:

James’s Newsletter.