Crossing the Hakone — One false step leads to the bottomless ravine!

In 1601, Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Five Routes of Edo and set up post stations along them, connecting his new capital of Edo (present-day Tokyo) with the other provinces of Japan. One of the old routes was the Tokaido, and the 8 ri (32 km) section between the post stations of Odawara-shuku and Mishima-shuku was feared as the most dangerous stretch, for it crossed the Hakone Pass, described as the “steepest in the world” in the folk song “Hakone Hachiri.” The Tokugawa shogunate designated this as a key area for defending Edo and built the grandest stone pavement in Japan, teahouses, a sekisho checkpoint, and roadside trees for the travelers.

PAPERSKY invited British Kat Chetram to join our journey of the Hakone Hachiri. Our trek started at Odawara Castle. Odawara flourished as a stronghold of five generations of the Hojo clan. Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s siege of Odawara in 1590 brought about the fall of the Hojo and the end of the century-long Sengoku period of civil war. The territory was then awarded to Ieyasu and played a prominent role in the defense of Edo until the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868. Odawara-shuku was established in 1601. Though only the ninth stop from the terminus of Nihombashi some 80 kilometers away, many travelers sought lodging here before crossing the tough Hakone Pass. Hence, Odawara-shuku became one of the largest post towns on the Tokaido, counting as many as 95 inns by the late Edo period.

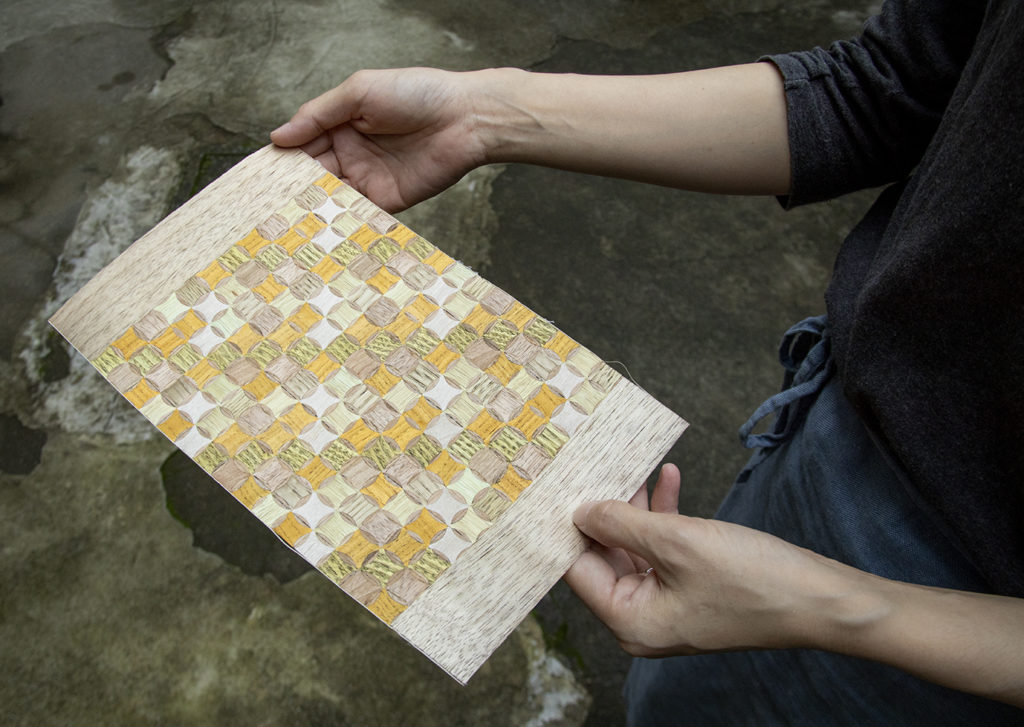

Odawara is a fun place to explore for traditional Japanese snacks and crafts. We bought some uiro steamed cakes for the road—the recipe is six centuries old—satiated our appetite with freshly made kamaboko fish cakes, and before going on our way, stopped at a yosegi marquetry studio. Rods of various types of wood are assembled into a mosaic pattern and planed to create a decorative veneer for furniture and other interior objects. The technique was introduced from Shizuoka in the second half of the 19th century and became particularly well-known in the post station of Hata-juku, between Odawara-shuku and Hakone-shuku. But because the history of woodworking goes back further in Hakone, yosegi was combined with techniques like hikimono wood carving and zokan damascenin to be known collectively as Hakone woodworking. Russian matryoshka dolls are said to have taken a hint from Hakone’s ireko nesting technique.

As we neared the Hakone Pass, the slopes grew steeper and an icon of the merciless crossing of Hakone came into view: the stone pavement. Before this path was constructed in 1680, the knee-deep mud after the rain was a torment for travelers. After construction, the conditions were not a whole lot better, as the rain left the path as slick as if it had been oiled, and this caused a spate of accidents where travelers were thrown off their horses or sent sliding downhill. Beyond countless slopes with names suggesting peril, like Oikomi “last spurt” Slope and Sarusuberi “slippery monkey” Slope, a rare line of roadside cedars came into view. The Tokugawa shogunate planted pine trees for travelers on the Tokaido, but because Mt. Hakone was not suitable for growing pines, cedars were planted in this area instead.

At Lake Ashinoko, we visited Hakone Sekisho, dating back to 1619. Koichi Owada, the manager, says that out of the 50-odd sekisho checkpoints nationwide, the one in Hakone most faithfully reproduces the original structures, construction techniques, and materials. The current facility is a full restoration based on detail drawings that were discovered of a major renovation project in 1865. The imposing black-painted buildings certainly reflect an Edo-period appearance. Even structures designed to guard against invasion are reproduced, like the lookout taking advantage of the natural vantage point.

Another must-see around Lake Ashinoko is Hakone Shrine. The red torii gate against the copious Lake Ashinoko and Mt. Fuji—commoners of the premodern era flocked to admire this picturesque view. On this day, we followed up our prayer with a walk along the west coast section of the trail around Lake Ashinoko. The 12-kilometer route covers two flood gates, a natural sandy beach, the quiet of the lake, and a vista of the mountains.

A change of scenery on the gentler West Slope

The next day, we departed Lake Ashinoko and made our way to Mishima. Compared with the East Slope, i.e., the Hakone Town side leading up to the Hakone Pass, the West Slope on the Mishima side was significantly more manageable. The view was good, too—we caught glimpses of Mt. Fuji as we made the gentle descent. Past the ruins of Yamanaka Castle, built on the slopes and destroyed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and the fields cultivated by Shinden communities, the pines lining the approach to Mishima Taisha Shrine came into view.

Mishima long flourished as a shrine town around Mishima Taisha. As the eleventh post station from Nihombashi, Mishima-shuku was an important hub of transportation with the Tokaido, Shimoda Kaido, and Koshudo roads intersecting in front of the shrine. The city of Mishima is also dubbed the “city of water,” as it draws spring water from both Mt. Fuji and Hakone. Streams flowing throughout the city serve as recreation spots for the residents. Daisuke Honda,handles a variety of projects including guesthouse production at a local construction company. We asked him to be our guide.

He says the city’s water supply ran dry from the 1960s onward and exacerbated the pollution of the Genbeigawa River. Mishima residents led a slow but steady move to improve the environment and restore the clear streams. The result is what we see today—Genbeigawa is the healthy habitat of the endangered Hotoke loach (Lefua echigonia) and an aquatic plant called the Mishima Baikamo (Ranunculus nipponicus var. japonicus). Even now, every resident continues the efforts to conserve the precious spring water.

In the old days, travelers who crossed the Hakone Pass celebrated their success at this location. Having heard that, Lucas and Kat followed suit and drank a toast with fresh water from a nearby tap. The custom of celebrating the crossing of Hakone faded in the Meji period of modernization. But after a day’s journey through the mountain on foot, the spring water must have tasted like nectar to PAPERSKY’s two travelers.