Hiroshi Yoshida’s Japanese Alps

In June, Kamikochi was completely transformed into summer. The looming mountains above me stood out in contrast with the grayish-blue rock surfaces and white lingering snow, and as the light fell through the fresh air, the lingering snow glowed whiter yet.

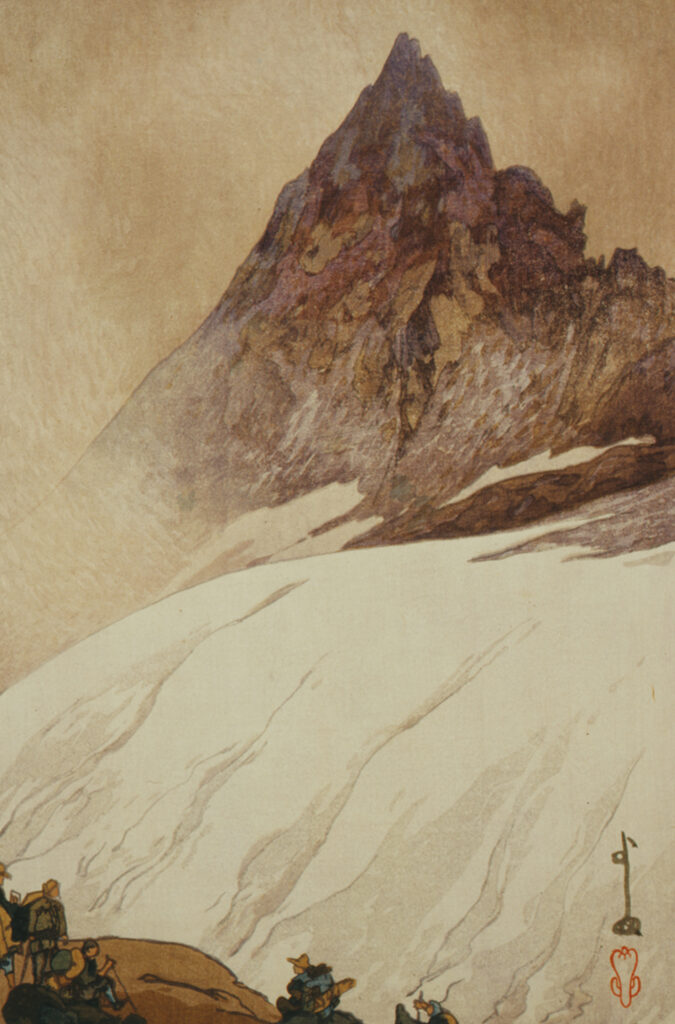

A symmetrical triangular rock peak pierced the heavens. Since the arrival of modern mountaineering, Yarigatake has remained enduringly popular with climbers. Mountain landscape painter Hiroshi Yoshida also loved to paint this peak, and had a mural panel of his own work entitled “Yarigatake and Higashikama Ridge” displayed in his living room.

He characterized Yarigatake as follows.

The Japanese Alps, with Yarigatake at the center, are home to some spectacular cliffs that could be called exemplars of precipitous cliffs.…(omission)…The cliffs of Yarigatake are a spectacular sight, with countless crevices running lengthwise and crosswise all over the cliffs. And these descend from the top of the spear far down to the Takase River.

As in his book – “On the Beauty of High Mountains‘ – he records his principal traverses: ‘From Shimajijma, via Kamikochi to Yarigatake. From Nakabusa to Kamikochi via Yari and Hotaka. From Maki to Kamikochi via Jonen and Yari. From Omachi to Kamikochi via Karasuboshi and Yari,” indicating that Yarigatake was an important part of his mountain journey.

The sunlight streaming through the young leaves brightly illuminated the Anemone flaccida that bloom like a carpet under the mighty Japanese elm trees. The forests in early summer are coloured with a wide variety of flowers, including ezomurasaki and violets. My sweaty back was met with the fresh breeze crossing the Azusa River.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

The day after I pitched camp at Yokoo, I followed the trail along the Yarisawa stream with clear snowmelt running through it. The valley was filled with the crisp, early morning air. The Anemone flaccida petals have closed up, their heads seeming to have drooped in the morning dew. At the far end of the valley, the lingering snow-covered mountains appeared pale and phantom-like in the morning sun. Eventually, light began to shine into the deep valley. Encouraged by the strong sunshine on my back, I ascended the long path leading to Yarigatake.

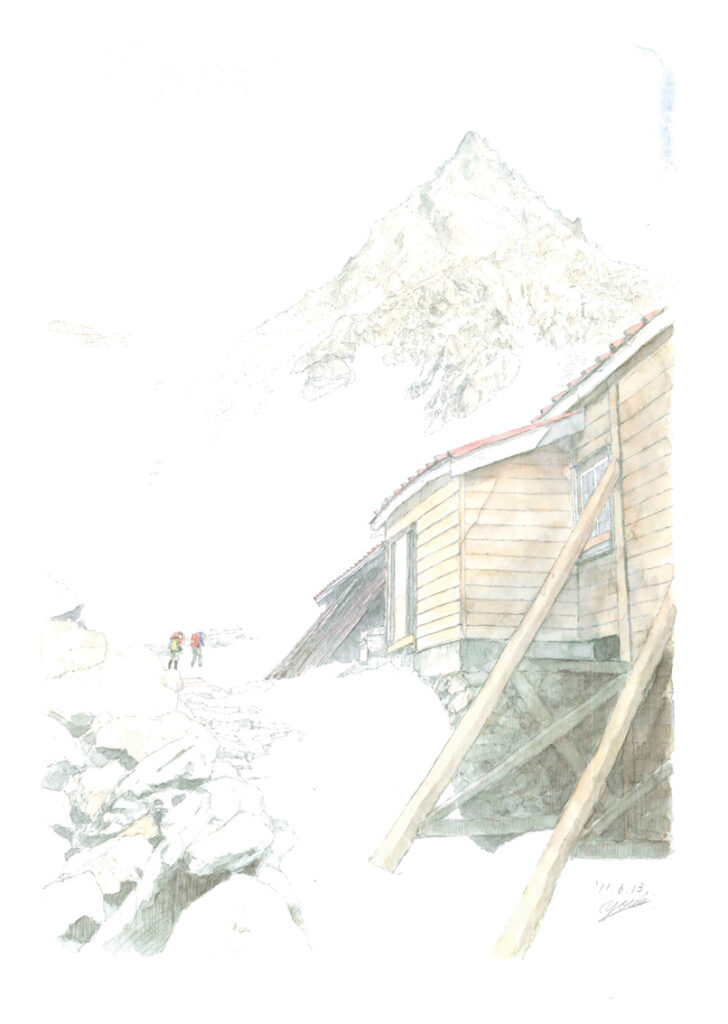

As soon as I left Yarisawa Lodge, I could just make out the tip of Mt Yarigatake protruding behind the folds of the mountain shadow; the summit was still a long way off. The view opened up when I reached Babadaira, the site of the Yarisawa Lodge’s predecessor, the Yarisawa Hütte (called the Alps Ryokan in Hiroshi’s time.) The snow-covered valley continued to undulate, with crevices opening up everywhere. Skirting, or rather jumping over the cracks, I took steps up the snowy corridor, taking care to avoid falling rocks. As the valley gradually opened up, the ridge came more clearly into view. Fresh snow must have fallen a few days ago. The snow here was brown, but near the ridge it was pure white, and the whiteness lent a clean blue color to the gray rock. I could discern three black forms in the middle of the wide snow surface. As the incline increased, it was time to take out the crampons.

Hiroshi Yoshida traveled to mountains around the world, including North America, the European Alps and the Himalayas, to paint their landscapes. Yarigatake is known as the ‘Matterhorn of Japan’, so how did he view the Japanese Alps, having also painted the Matterhorn in Europe? He left the following description.

There is a man who claimed to have seen the alpine plant Edelweiss flowers of the European Alps at Ontake in Kiso. He then went on to explain that the Japanese Alps were very similar to the Alps of Europe in terms of alpine flora. I believe, however, that it is not necessary to stress the similarity of the Japanese Alps to the European Alps to that extent. I think that the presence of the genus dicentra and the Phyllodoce nipponica is enough, without having to specifically identify the edelweiss flower.

For Hiroshi, the Japanese Alps did not play second fiddle to foreign mountains, but were rather a unique mountainous region superior to them. “The beauty of Japan’s high peaks, which we can boast to the rest of the world, is that they are well wooded and show beautiful changes from season to season.…(omission)…Another feature of Japan’s alpine beauty is the crystal-clear water of the valleys that weave between the mountains. I have seen many valleys in other countries, but never have I seen water as clear as that of Japan.” As he notes, he had an objective view of the features of the Japanese Alps. It struck me that for him, Yarigatake was not the ‘Matterhorn of Japan’. Similarly, suffice to say it was not solely the scenery but surely the irreplaceable people with whom he climbed that made the Japanese Alps such a special place.

Before long, Yarigatake rose up in front of me, looming larger with every step. Just below the summit, the Yarigatake Hütte was visible, and below it, the Sesshō Hütte. Comparing Hiroshi’s print ‘Yarigatake’ with the landscape in front of me, I realized that it was painted from the vicinity of Sesshō Hütte or the slightly higher Higashikama Ridge.The Sesshō Hütte (then Sesshō Koya) was opened by Kisaku Kobayashi in 1922. Kobayashi was a man whom Hiroshi admired as “a good-natured and extremely endearing man”, and whom he put his absolute trust in and asked to guide him whenever he hiked in the Japanese Alps.Two years before Kisaku opened this mountain lodge, he established the Kisaku shindō (“New Trail”), which leads from Mt. Otensho to Yarigatake via Higashikama Ridge, and is said to have been named by Hiroshi. However, just a year after opening the lodge, Kisaku was crushed to death in an avalanche. That was three years before Hiroshi published his “Twelve Scenes in the Japan Alps”. When I surveyed the landscape in front of me while trying to imagine Kisaku, I couldn’t help feeling that the place where ‘Yarigatake’ was painted – whether Kakusei Hütte or Higashikama ridge – contained some homage to Kisaku. Hiroshi climbed Yarigatake with Kisaku and admired this landscape together. For him, the Japan Alps were not only a place where he searched for themes for his paintings, but also an unforgettable site where he traveled many times with the people he loved.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

A plume of mist was beginning to gush up from the west. It apparently snowed two days ago, and there was crusty snow on the rocks leading to the summit, which had melted in the summer sun. Climbing up the mixed zone with my crampons on, I reached the summit shrouded in white mist. Through a faint break in the clouds, I could make out the endless range of rolling mountains with abundant lingering snow. The mountains at the headwaters of the Kurobe River, the innermost of the Northern Alps. One of the mountain ranges, which was soon drowned out by the dense mist of gas, was bound to be Mt. Washiba, the final destination of the trip around the “Twelve Scenes in the Japan Alps”

<PAPERSKY no.36(2011)>

route information

Yarigatake has been renowned as a mountaineer’s dream throughout the ages. This time I came in early June, but during the lingering snow season you will need ice axes and crampons with at least 10 prongs.The general climbing season starts in late July, after the rainy season has ended. The journey from Kamikochi to Yarigatake-sanso Lodge is long, so an overnight stay at Yokoo or Yarisawa makes for a more comfortable trip. Yarisawa is a long, gentle ascent, but there are no technically difficult sections. The final ascent to Yarigatake is rocky with a series of scrambles and ladders, so tread carefully. Note that the routes are different on the ascent and descent. Kisaku shindō is a popular route on the Higashikama ridge from Mt Otensho to Yarigatake. One can traverse from Mt Jōnen and Tsubame to Mt.Otensho, so by all means please try this route.

Yohei Naruse

Born in Gifu Prefecture in 1982. Graduated Tsuru University, Graduate School. Following a stint in advertising, he currently works as a freelance writer and illustrator.