A Unique Mountain Sketching Method / From the Summit of Mt.Shirouma

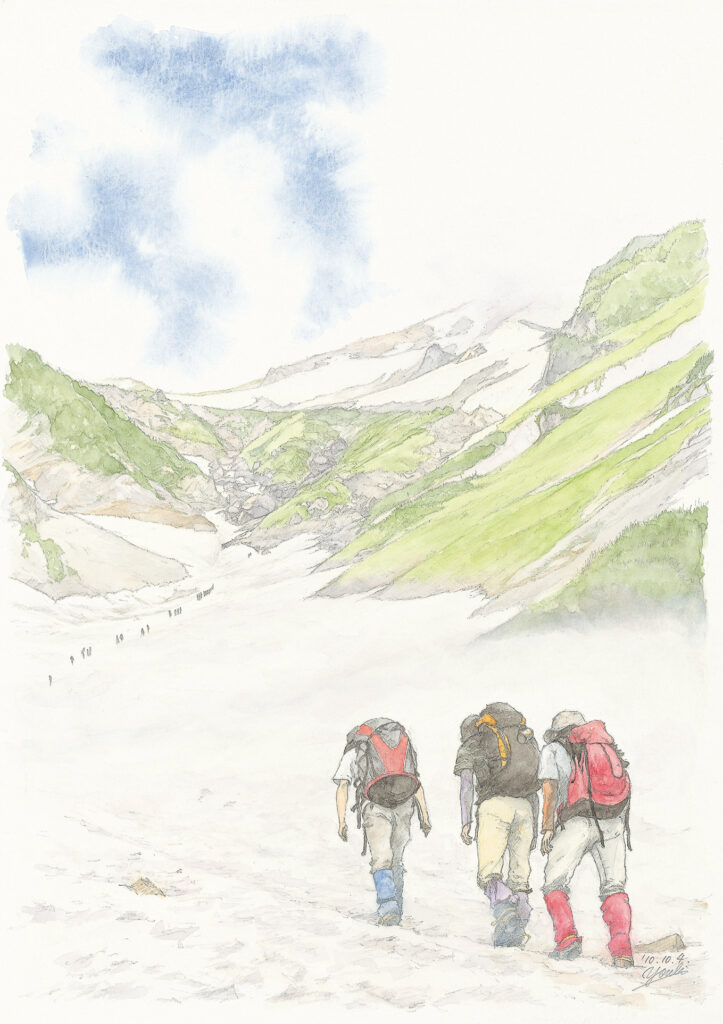

The Daisekkei (Mt.Shirouma Snow Field) ran deep into the layered ridge. The chilly wind turned the snow into a white, cold mist that crept across the surface of the snow. As I ascended, the valley was shrouded in mist; I followed a single path carved into the snow as if swimming in a sea of fog.

Hiroshi Yoshida went into the mountains not to climb, but to sketch. When he found a suitable place to do so, he set up his trusty tent and made a base, camping out for days until he was satisfied with the mountain scenery he had captured. Once finished, he would pack his bags and wander the mountains anew in search of beauty. Since the summer peaks often clouded over during the day, he would sketch from around 4:00 to 10:00 in the morning and then again in the evening when the skies cleared up. He not only made light-colored sketches, but also carried large canvases round and painted in oil on site. The main pieces that Hiroshi took with him were No.12P and No.8P, the largest dimensions that he could draw on site. Although these were masterpieces in their own right, he used them as the basis for larger paintings in his studio, which he exhibited in numerous exhibitions.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

Traversing the steep snow surface, a whole field of flowers appeared: Anemonastrum narcissiflorum, Geranium yesoense, Trollius shinanensis… The light descending from the blue summer sky makes the flowers appear even more lively and brightly lit. When I arrived at the lodge soon after, I could make out the low roar of thunder in the distance. By the time I set up the tent, the area was enveloped in thick fog and small raindrops began to fall. The thunderstorm intensified and strong winds pounded the tent. When you are trudging along a mountain trail for hours on end, no matter how stunning the scenery may be, it takes a lot of effort and is actually difficult to put down your pack, take out your sketchpad, and draw a picture. And if you stay there and paint for hours, the sun will set before you reach your destination.

You can’t paint if you’re puffed out from walking. Knowing this well, Hiroshi took great care not to expend his energy required for sketching. “When you are on the mountain and the weather lasts for several days, you must paint as much as you can, and so if you use up all your energy at that time on walking you will waste a great deal of time.” He slept well the night before, walked at a modest speed and had his luggage carried by laborers, not carrying a single paintbrush with him. Instead, once he picked up a brush, he was “as busy as on the battlefield,” fighting fatigue “more intense than when walking,” and finished the painting in “one vigorous stroke”. He was also careful to keep his baggage lightweight: “A painting rack or a tripod might be useful, but I would never take them with me. Even for a box of paints, it is best to choose something as light as possible, and to have each person consider only what is necessary.” Hiroshi Yoshida strove to conserve his physical strength in order to paint to the fullest. But that was not the only secret of his sketching; his eldest son, Tōshi Yoshida, who accompanied his father on a sketching trip to India, explained as follows.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

“My father painted very quickly, one in the morning, one in the afternoon, a No. 8P or 12P oil painting, and one or two light sketches for prints. Even No. 25 was finished in two days, half a day at a time, and it would be a detailed, realistic landscape painting. During this time, he would make a number of sketches of incidental people in the background. Watching my father paint in oil, he would first draw the contours with a brush, adjust the composition to perspective, and then begin to paint the definitive subject matter. The colors would follow in sequence, and when they were all filled in, the painting was complete. He would paint each section ensuring that there would be no need to repaint or revise it.”

Normally, a painter starts with a distant view and gradually paints a foreground view, but it is said that Hiroshi started his painting from the lower left corner of the screen and completed it when he reached the upper right corner after passing through the center. He had developed a unique method of sketching that enabled him to paint at an astonishingly fast pace. This method must have been very efficient in his mountain sketches as well.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

“You can’t sketch a mountain unless you have done it before. And you can’t sketch a complete picture just by climbing a mountain once or twice. To draw a clear and coherent picture, you need to produce a large number of sketches. The funny thing is that the way you sketch down there is not the same as up in the mountains and requires a lot of practice and research.”

Fascinated by the ephemeral beauty of alpine light and clouds, Hiroshi tackled this difficult-to-express motif head-on. Practice and research entailed keen observation of the shifting rays of light and clouds, and responding to these changes to quickly capture on canvas the fleeting beauty that the mountains presented. By holing up in the mountains as a kind of hermit, he was able to acutely experience “a kind of pure and spiritual ambience unique to alpine mountains.” It was this approach together with his peerless and rapid sketching method that captured the ephemeral beauty of the alpine landscape, and gave rise to his bold yet delicate style of expression. His insistence on practice and study is typical of the artist who was known as the “devil of painting,” and who never skipped a beat in his training.

Peering out from my tent, I noticed intense crimson clouds fluttering thinly in the pale azure sky. Bathed in the white morning sun, I climbed up the craggy terrain leading to the summit of Mt.Shirouma. As I neared the hut, I looked back and saw Mt. Shakushidake and Hakuba Yari looming large in the distance, beginning to turn orange. Then, beyond Hakuba Yari, I spotted a sharp triangular peak in the blue mountain range in the distance – Mt.Yari. In the upper right corner of Hiroshi’s print “From the Summit of Mt.Shirouma,” a distinctive sharp-angled mountain is depicted. It was blindingly obvious that the mountain was Yarigatake. The landscape he portrayed more than 8 decades ago was now quietly unfolding before me, looking exactly as it had done back then. I felt that the steep peaks, which seem to be somewhat accentuated in the painting, expressed his excitement at being able to gaze at his favorite mountain.

The sun was fully up, marking the beginning of a crisp summer day. Looking down at my feet, I saw the bluish-purple of the Aquilegia flabellata smudged white in the cool morning dew.

<PAPERSKY no.34(2010)>

route information

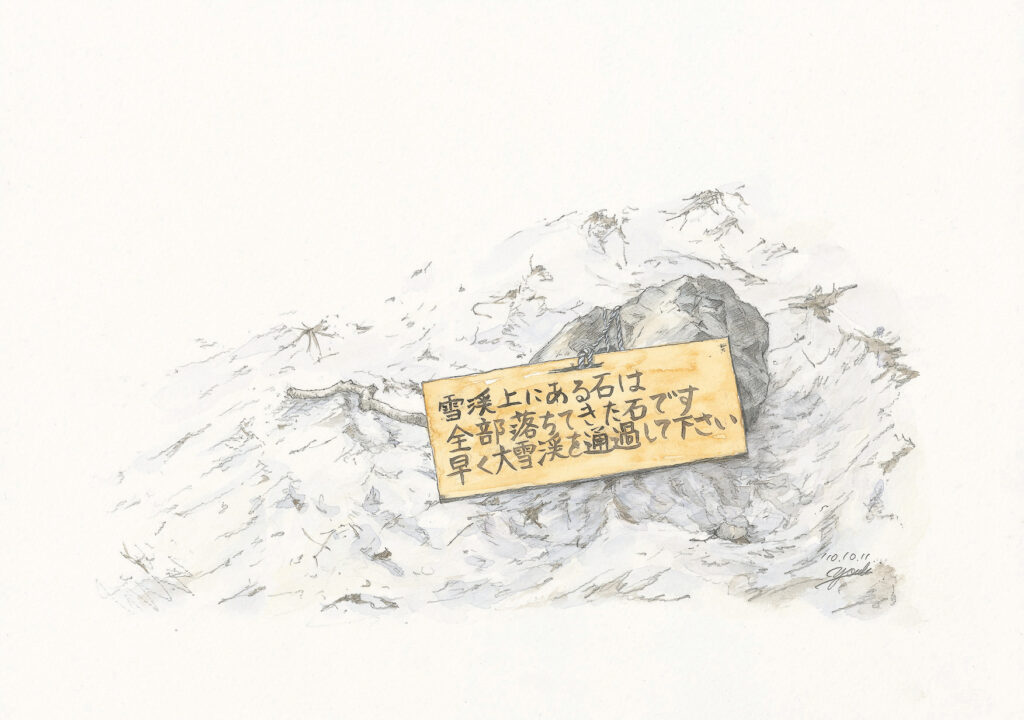

Shirouma Daissekei is the largest snowy valley in Japan. The route changes depending on the snow melt, and the autumn route is often preferred as the snow slopes are narrower and there are more crevasses at that time of year. Light crampons and trekking stocks are recommended for early morning when the snow surface is icy, and for those who are not accustomed to walking on ice-covered slopes. Light crampons can be rented and purchased at mountain lodges around Daisekkei and in front of Hakuba Station. The snowy ridge is flanked by brittle cliffs, with collapses and falling rocks a common occurrence. In particular, falling rocks in the snowy valley require the utmost caution since they are not audible. One should pass through the snow line as fast as possible. Mt. Hakuba is also a treasure trove of alpine flora. Climbing up the snow-covered ridge, you can feast your eyes on multi-colored fields of flowers, which are in full bloom during the summer months. The tenting area is located at the Mt.Shirouma summit lodge, built at the junction of the ridge line. Shirouma-sō is the largest mountain lodge in Japan and even has its own restaurant.

Yohei Naruse

Born in Gifu Prefecture in 1982. Graduated Tsuru University, Graduate School. Following a stint in advertising, he currently works as a freelance writer and illustrator.