A conduit between nature and humanity

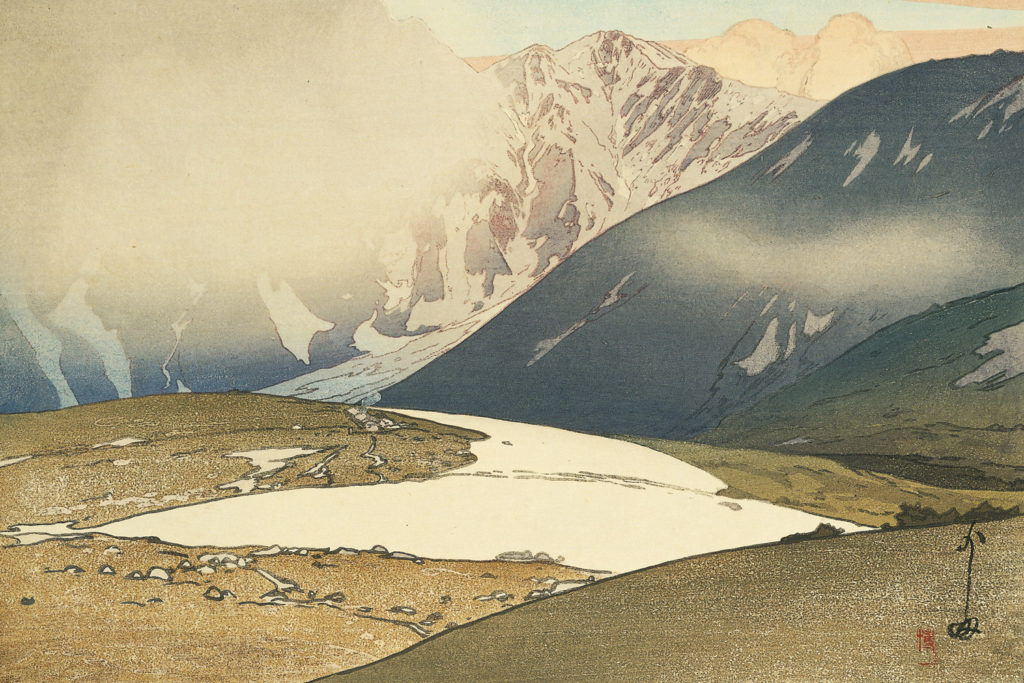

I step onto the ridge, which is soaked in the bracing rays of the morning sun. Straight ahead, the exposed rock faces of the Tateyama Range stretch out imposingly, like a fortress in the sky. Tinged with the morning sun, the dense fog emits a pale amber hue, and once enveloped in it I feel as though I have stepped inside the light, faint as it is. Down below is the expansive Murododaira, characterized by vivid green grasslands, yellow sulphur, and white grit. Below that, the view is obscured by thick grey clouds. By the time the sun is high, the rain clouds will have covered the ridge.

Tateyama is revered as one of Japan’s three holy mountains along with Mt. Fuji and Mt. Haku and has been climbed for religious purposes since the late Nara period. Murododairia, which serves as the base for mountain climbers, still houses Japan’s oldest alpine guesthouse facility, “Tateyama Murodo”. While it is unclear as to when it was built, there is a record of it being restored in 1617, meaning that it certainly existed prior to then.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

In the period from around the end of the 1800s to early 1900s, Japan’s mountains played host to a gradual rise in “modern alpinism” which contained many sporting elements imported from Europe. Engineers and missionaries who came to Japan from Europe were able to attempt mountains in Japan using their mountaineering skills polished in the French and German Alps. These included British missionary Walter Weston who took on many peaks in the Japanese Alps and published “Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps” (1896) in London. Following Weston’s rallying cry, some Japanese people founded the nation’s first ever mountaineering body, the “Japan Alpine Association” in 1905, which brought a zeal for mountaineering to the masses and made peaks and crags more accessible to more people than ever before. In the early Taishō era, landscape artist Hiroshi Yoshida energetically ventured into the Japan Alps, when this mountaineering zeal had become entrenched.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

illustration | Yohei Naruse

Having approached from the Hayatsugi River and traversed Mt.Tsurugi, Yoshida and his group would have pitched camp in Mita Taira, where the Tsurugisawa Hut is today. They had intended to traverse the Tateyama ridge the following day, but gave up due to intense wind, and after flattening their tents and securing them with heavy stones, made their way down against a strong wind to Murodo. Rain greeted them upon arrival to Murodo. Hordes of mountain climbers were trudging through the rain and arriving in Murodo, only to then continue along their journey into the rain. Such behavior exhibited by mountaineers would have perplexed Yoshida, who had come to the mountains to savor their beauty and put pencil to paper.

“When it comes to scaling mountains, each man has a different objective. Some climb for religious purposes while chanting sutras, some do it as a form of sports or perhaps for research, for health, or merely for the spectacle of it. Whatever the reason, there is nobody whose soul is not stirred by the beauty of the mountains. Yet I find it hard to condone those who climb mountains exclusively for sport and for whom appreciating the beauty of the mountain is a secondary concern, climbing only to satisfy some peculiar sense of superiority and lust for adventure, only to end up meeting an untimely demise due to their ill-conceived quest”.

A forced march through the rain while battling exhaustion is not only dangerous but defeats the whole object of enjoying the “beauty of mountains”. If it’s raining, better to hunker down and wait for the clouds to clear. This was how Yoshida approached mountain treks. So, what exactly was the “beauty of the mountains” as he saw it?

illustration | Yohei Naruse

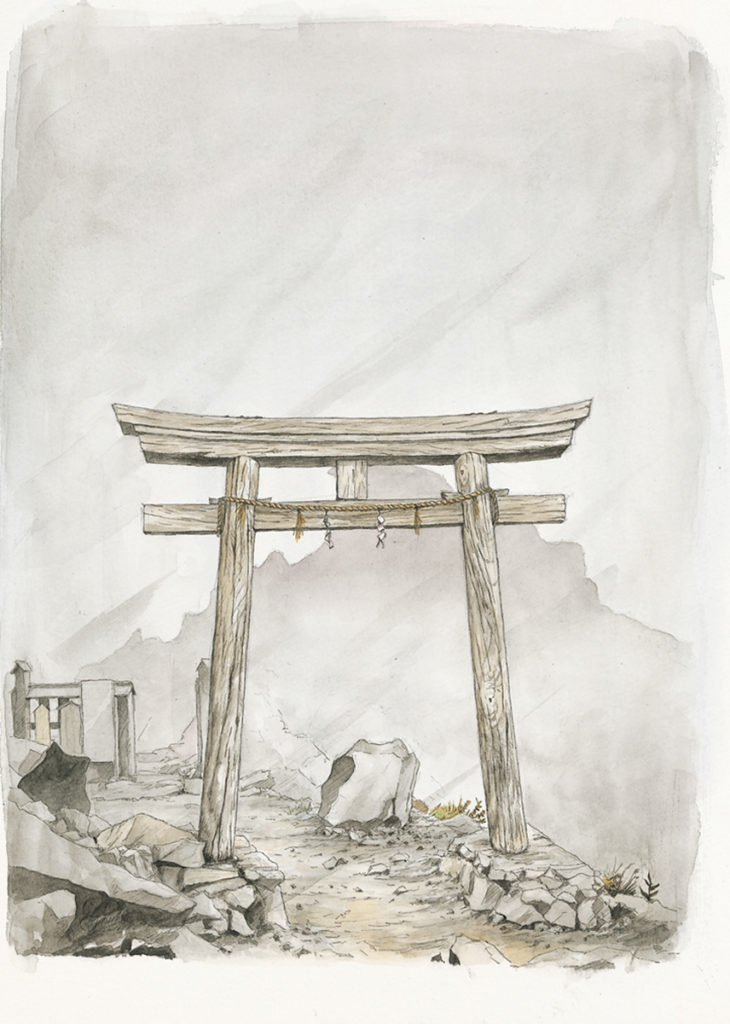

As expected, the ridgeline is cloaked in a dense and ominous fog. Inside the tranquil clouds that offer no view, the only sounds I hear are the buffeting wind and the rasping gravel as I tread over it. Following several gently undulating peaks, the route finds its way through a series of giant boulders. The faint sound of the Taiko drum means I am close to the Oyama Peak, with its Shinto Shrine built at the peak. The chief priest bangs the drum to cleanse worshippers. I climb through the gate and upon climbing the stone stairs, arrive at enshrinement. Dense fog looms all around, meaning there is no view at all.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

“Upon reaching the summit, we leave the human realm far behind and are possessed by a sensation of approaching the realm of the divine. An ambiance of purity abounds, that could be said to be unique to the high mountains. Then in the distance far beyond the rows of peaks, one catches sight of a basin, in the realm of the mortal. At this point we cannot help but be struck by the might of Mother Nature. With this comes the profound realization of the awesome beauty of high mountains”.

The “Beauty of high mountains” espoused by Yoshida is the beauty of mountains shrouded in the mysterious presence of the sublime, which cannot be experienced in the terrestrial world. He saw it as his vocation to channel this beauty and to reproduce it in the form of a picture. As he put it, “A painter’s lifework is to stand in between man and nature, and for those not fortunate enough to witness it themselves, to reproduce the beauty of nature and to show it to them”. To be a painter meant to be a conduit between the natural realm and the human, something close to being able to surpass the limits of men and to step into the realm of the divine. The same might be said of itinerant Buddhist monks and their ilk. The “Yamabushi” forced their way into the mountains and by performing ascetic practices were said to have acquired supernatural power. While it is unclear as to what exactly this supernatural power constitutes, in Yoshida’s case it could be said to be his ability to express the subtle and profound ambiance omnipresent in his works. This was a sharp intuition tempered by the mountains, upon a foundation of an indigenous worship of nature that existed before religions were systemized, an almost transcendental skill mastered through endless practice and investigation.

illustration | Yohei Naruse

Negotiating the steep descent, stepping onto the ridge that leads to Goshokugahara I notice that the bustle around Ooyama has amazingly dissipated. The dense fog has turned into water droplets, which gradually augment until they begin to form a pattering on my waterproof layers, upon which point a flock of ptarmigan appear at the base of a Pinus pumila tree. As if being shown the way by these fowl that are said to conjure up thunderstorms, I step gingerly into the dense fog.

<PAPERSKY no.28(2009)>

route information

Tateyama is a general term for several peaks, the highest of which is Mt.Ōnanjiyama (3,015). The 3 peaks of Tateyama are Mt.Jodo (2,831), Mt.Ooyama (3,003), and Mt.Bessan (2,874). Tateyama also refers to Oyama Shrine located by the Oyama peak. While this time I transversed the ridge from Mt.Tsurugi to Mt.Bessan, there is another route that goes from from Murodo past Ichinokoshi Hut and then directly up Mt.Ooyama, taking just under 2 hours. While the latter part is quite steep, there is no major exposure, and you can hike with relative ease. There is a bus up to Murodo-daira at 2,450m, bringing 3,000m mountains well within reach. It is also known for having an upper section white with snow, a mid-section red with leaves and a lower part that is verdant green. Japan’s oldest alpine accommodation “Tateyama Murodo” stands next-door to Murodo Hut, and these days is a historical museum. When Yoshida laid his head here, there were said to be 200-300 people all bunking down at once. It’s just as popular now as it was back then.

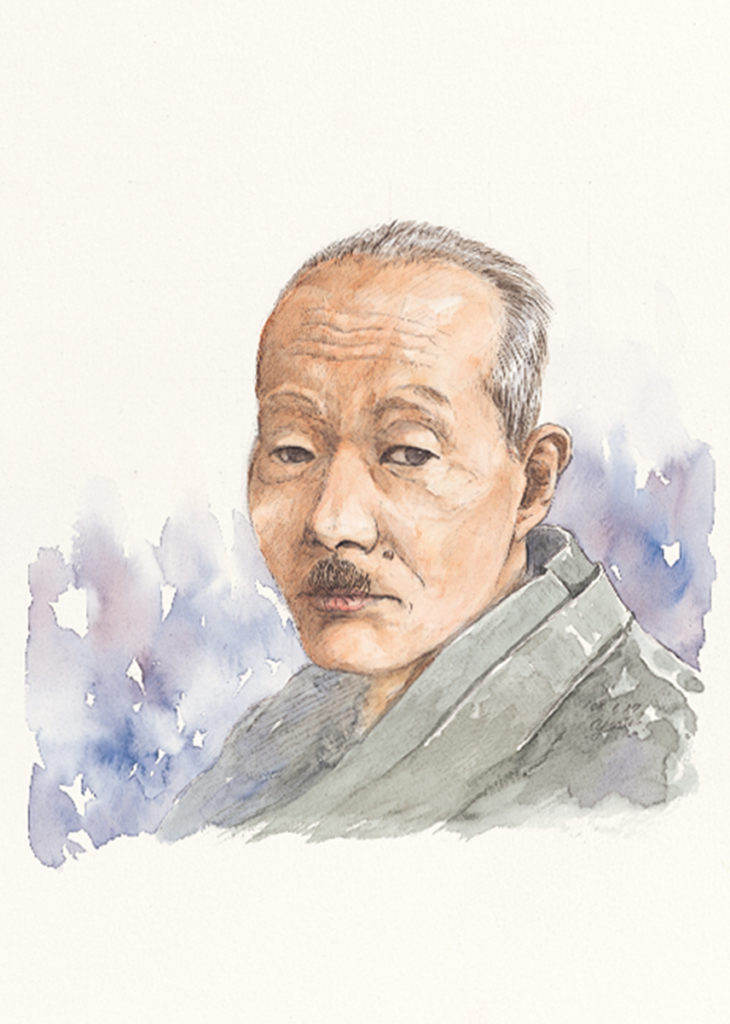

Yohei Naruse

Born in Gifu Prefecture in 1982. Graduated Tsuru University, Graduate School. Following a stint in advertising, he currently works as a freelance writer and illustrator.