“Mountain Gear Project is a collaborative artwork between Hiking & Architecture.”

The first time I saw this curious little green tent by mikikurota architects, I was struck by its sophisticated design. What inspires this husband and wife team to design some of the most functional and beautiful outdoor gear in Japan, perhaps the world?

This is my journey to discover how an architect goes from designing houses to designing tents?

When I think about architecture and tents I remember one of my favourite houses in Japan: Mountain Research somewhere in the hills of Kawakami, Nagano Prefecture. But this is a house with a tent feature, although beautiful and in celebration of nature, I think the sentiment behind the design is somewhat different from mikikurota architecture’s refreshing approach.

On that day during our biannual hiking/camping event『比良de宴会!』(Hira de Enkai!) I wasn’t expecting to be so surprised by the design of a tent. Being used to hikers sleeping in all manner of structures and coverings —home-made to brand-made— from designs that suspend floating between trees, or lean at varying angles at varying heights above the ground, those pulled taught between found sticks or bicycle wheels, mathematical constructions standing rigid in an assortment of geometric forms with poles straight, curved or a combination of both, and some no more than bags on the ground, crawled into at night.

Personally I prefer a sealed tent for private sleeping with mesh for letting air in and insects out. I’ve slept in many over the years, from early days of sharing heavy canvas tents with school friends, to building makeshift bivouacs in the woods as a teenager —ferns on the ground for bedding and all.

Inevitably as the cityscape replaced my view and work filled my time. Ideas of camping adventures were almost forgotten. Luckily my enthusiasm was reinvigorated with a move to Japan. Only then did I realise that years of inner-city living had led me away from my love for the outdoors.

I immediately went out and bought not one, but two tents.

After a few flash starts —completely miss-reading Japanese maps & totally underestimating typhoons— I accidentally found myself amidst the ultralight backpacking community I previously knew nothing about. The minimalist hiker aesthetic had always appealed to me so I was naturally drawn to this fast and light way of moving through the landscape. Not to mention the simple multifunctional gear, much of which was designed and made locally by enthusiastic individuals and small brands. The mainstream brands I had sought-after since the 80’s, were in my designer’s opinion being left behind by these lighter, brighter and more interesting small garage brands. It was also encouraging and inspirational to see that the communities behind these brands literally had their feet on the ground and hands on the rocks and were actively creating products based on experience.

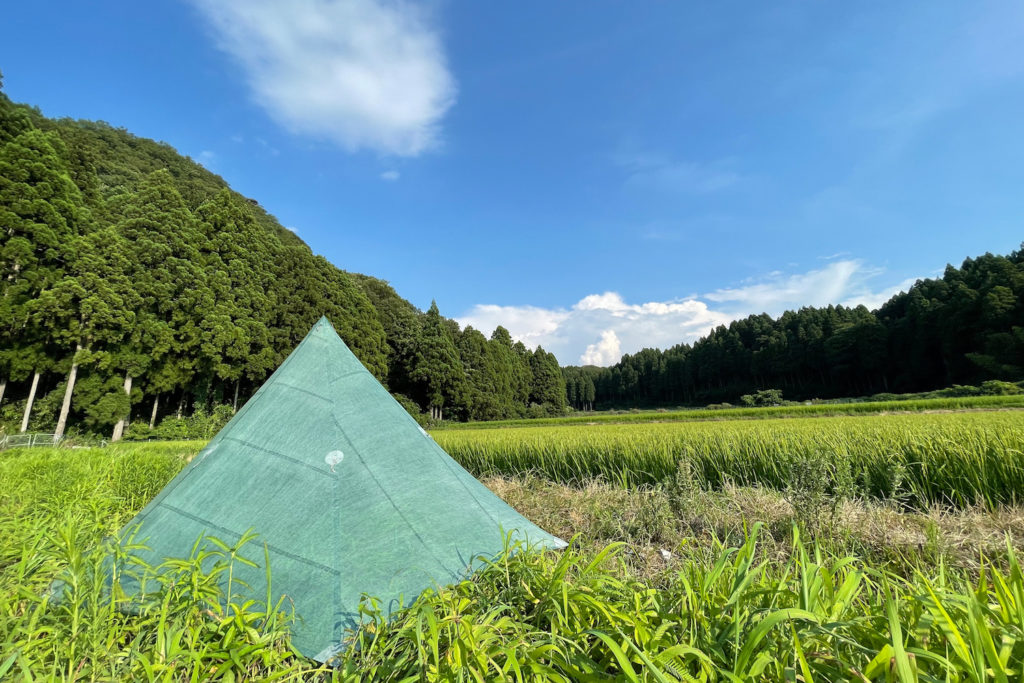

So on that summer evening, when I first caught a glimpse of that mikikurota Elemental 1 shelter.

It blew my hiking socks off!

The usual revelry of a group of hikers around a campfire commenced late into the night, until one by one retiring into our preferred shelters. Packing up the next morning and hiking in our respective directions. The design detail of that shelter switchbacked in my mind as I walked switchbacks to my car. From that day until now, I couldn’t get this curious little green tent out of my mind.

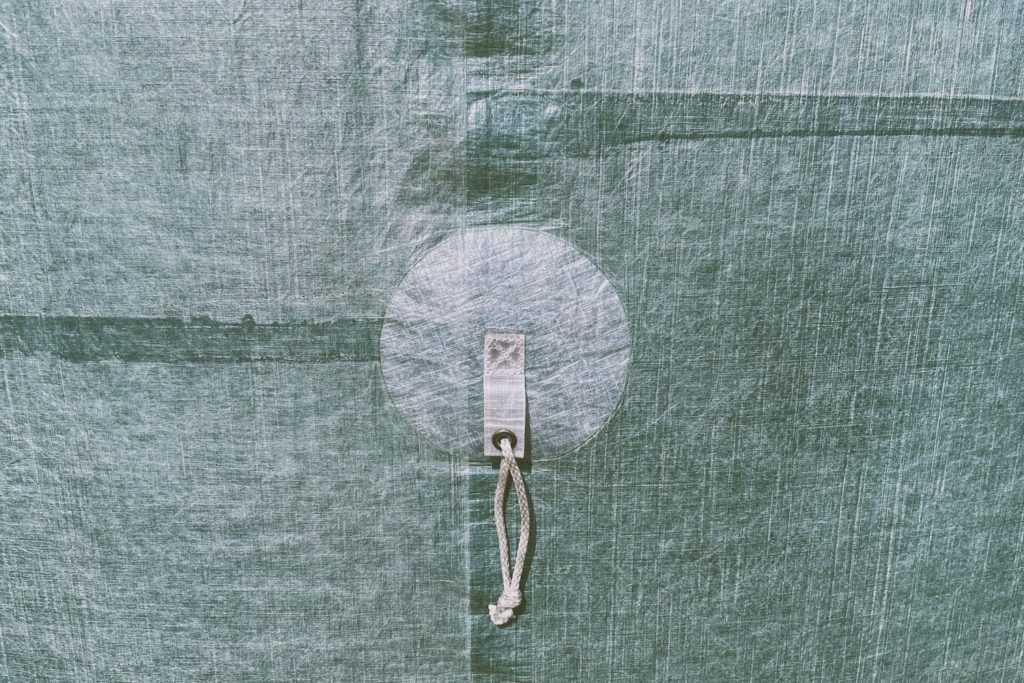

I was familiar with Dyneema Composite Fabric (DCF) —Cuben Fiber as we called it back then— having supported Jan Chipchase in the development of his iconic D3 Traveller duffel. At the time I was using a laser machine to cut patterns from DCF for my own micro hike/run wallets. However, my efforts to make my own gear was nothing in comparison to the level of design detail and craftsmanship I saw in that DCF shelter. It’s bonded —not sewn— seams, zippered ventilation with adjustable titanium bar and magnetic —yes magnetic— loops for securing the open doorway flaps. Unimaginable, unbelievable… and understandably a little expensive. I immediately wanted one!

The designer in me had to know more. What is… who is mikikurota? architects?

Shinpei Miki & Michiko Kurota —Miki-Kurota— make up the husband and wife team which is mikikurota architects.

They started working together for a competition in 2014, which they won, launching their company in 2015. A couple of years later, introducing their Mountain Gear Project (MGP) designing and making gear to support their outdoor activities, in creative juxtaposition to architecture. As architects they build using other people’s money, with other people’s help. With MGP, they wanted to experience and express the opposite: building with their own money and own hands.

Now a few years later, Shinpei and I are no longer strangers, having crossed paths at several hiking community events. During which, struggling with obvious communication barriers, failed to talk more deeply about his designs. This Papersky series became the perfect opportunity to have that long awaited conversation via email & zoom. At last, getting the chance to ask “Why does an architect go from designing houses to designing tents?”

As I talked to Shinpei it became evident that this was more of a chicken and an egg type question. Not why an architect goes from designing houses to designing tents or from making tents to making architecture. More an ongoing parallel exploration into his creativity and his admiration for nature and being in natural environments.

Growing up in Tokyo, Shinpei fondly recalls winter skiing trips with his parents and summer holidays spent at his grandmother’s house in Hyogo prefecture. Where he enjoyed fishing in rivers and camping for the first time. He never wanted to be an explorer himself despite avidly reading books about fearless adventures and mountain explorers whenever he had the chance. Yet, through these books and family trips, he “intuitively felt there was a way to enjoy nature in a deeper way”. His love for fishing grew and persisted throughout his university years, on into work-life. He even began designing and making his own fishing lures, attempting to appeal to the changing mood and impulse of the fish via the designs. Admittedly not very good at catching fish, he enjoyed the process and was discovering a new and very satisfying way of approaching nature.

It was during this time he started making his own tents —using the lightweight material Tyvek— carrying them along on his adventures in search of Yamame (Cherry Salmon) Iwana (Char Trout) and Rainbow Trout in and around Tama river or the Kurobe headwaters. Catching & releasing most of the fish, occasionally keeping one to two for dinner. These would be cooked and eaten along with foraged plants, before spending the night in his homemade tent. For him, using tools made by your own hands and ingenuity, “is a way to feel more alive”. This was his way to deeply experience nature, as he puts it “through my own interface”.

“I think about the relationship between myself, architecture and nature.”

Now enjoying trips together, whether hiking onsen to onsen in north Japan’s Iwate Prefecture or around the mountains closer to home in Tokyo. It is these shared experiences in nature which admittedly inform their architecture practice. To them, architecture is an art form combining design and technology with a sense of adventure (interpretation of nature).

“Nature and architecture are so close together, that in fact I believe architecture to be nature.”

We agree that most people don’t think of their house as part of nature, more as something built to separate themselves from nature. Yet from a designers point of view, the act of designing a building is inextricably linked to the natural environment. The problem is that too many people don’t realise this. To Shinpei, it’s obvious that many people are needlessly missing out on a richness of life.

On a cosmic level there is no separation, no boundary between what is man-made or nature-made, however there is an interpretation.

“I believe the way we interpret nature is the way we create”.

Wanting to slowly convey this message through their activities, they feel in order to do so they need to express themselves across different genres. Although architecture is often their focus at work and in conversations, we shouldn’t assume that architecture is their sole measure of success. I was somewhat surprised and pleasantly refreshed to hear that Shinpei and Michiko see themselves more as artists: designing and producing everything from architecture to products. However as I studied their diverse range of projects, I found one common element throughout, regardless of scale or material: quality.

How do they interpret quality?

There is more to quality than just the materialistic value of something. Shinpei suggests that quality is something that is created from balance, and admits this is a problem he struggles with.

We discussed the quality of thinking; ideas, ethics and sensibility, quality of construction; design, technique & naturalness (gravity/geometry), and quality of materials; man-made and/or nature-made. Also a quality of life and that of relationships. Talking in these terms, their design is a subtle interplay of these elements to support an optimal or natural quality I think mikikurota is navigating towards.

I brought up the topic of their Mountain Gear Project, which I feel encapsulates everything we’ve been discussing so far. A house is often too big or too complex to be understood from a single viewpoint, whereas sitting in their Elemental 1 shelter —arguably flexible personal architecture— you can see every element of quality literally on the surface surrounding you. The thoughtfulness of function & use, the choice of materials & construction method, and the naturalness of gravity & geometry. Combined in such a way as to amplify the experience of being in any natural environment.

This is the shelter Shinpei takes on solo fishing trips or Onsen to Onsen hiking with Michiko, having enough space to comfortably sleep two. They also designed a larger ultra lightweight Banquet shelter allowing up to eight people to share a Nabe (Japanese hotpot) cooking experience outdoors.

And then smaller with no attention to detail spared, are their curious little Fruits Sack —again made of DCF in the same manner as their shelters. Closely inspecting these stuff sacks, I speak from my designer’s perspective when I say they are almost perfect — I have to say almost, because I’m secretly jealous of how beautifully perfect they are! Stuff sacks over the years —regardless of brand— have essentially remained unchanged — you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all! Then the cosmic universe turns your world upside-down by presenting you with a Fruits Sack!

I had to know more about the process behind the conception and construction of these remarkable products. During our zoom conversation, Shinpei explained how they came up with the idea.

“After having drunk at a mountain party, my friend let me eat a fresh apple. It was the best cool down ever. In the mountains, fresh fruits will give you the best time. So, I decided to make a fruit sack made using a combination of 20% practical / 80% humour.”

First making an Apple Sack as a gift for their apple-carrying hiking friend. Naturally as with all their projects, they wanted to make it following their design aesthetic. To do so, it required a new bonding technique to seal it’s original three dimensional construction. During the process they soon realised that apples aren’t the only fruit. People also like to carry oranges, sometimes melons… and we laughed at the prospect of a grape-sack! In this way a series of 5 Fruit Sacks were made from Mikan (0.2L) to Suika_Rolltop (8.5L) in 3 weights of DCF from 0.8oz (green) to 1.4oz (white).

“Fresh fruits are heavy but, in the Fruits Sack, do you feel the same heavy?”

Of course these sacks aren’t only intended to carry fruit, the larger Suika Sack are multifunctional, equally at home in the city as they are in the wild. To me they hold a sense of hope and joy that something so ordinary and unassuming as a stuff sack can —through thought, intention and attention to quality— be transformed into something unexpected and beautiful, both aesthetically and functionally.

We talked about how they reminded you of a Kamifusen (Japanese paper balloon). Once mentioned the resemblance is evident. Giving these sacks a distinct Japanese characteristic. Unintentional, yet present, hiding within the quality and details. This is true of not only the stuff sacks but in everything they produce. What I would call a subtle Japanese sensibility.

Wondering how they felt about this observation, did they feel that there is a Japanese-ness to their work?

They speculate that there probably is, but it’s not something they really think about when creating the work. Maybe it’s something best noticed after completing a project. For them, with each new project, they hope to discover their own uniqueness or perhaps their Japanese sensibility.

Shinpei commented that on a daily basis he’s not conscious of being especially Japanese, nor of a Japanese-ness of his designs. Yet, he does suggest that there is subtle Japanese coolness in their work and attitude. I interpret this as a calmness or fearlessness to try new ideas, pushing perceptions of what architecture is, while at the same time very much rooted in the practicality of human needs.

He frequently mentioned that design is not about making rules, it’s more about creating a space for conversations around sensibilities, ethics and respect. Feeling a need to communicate his message not only within our small world of design or Japan, but also to people on the other side of the world — through the medium of design. We agreed that it’s not enough for a Japanese designer to only appeal to a Japanese audience.

Now as we reached the end of this conversation, I wanted to know —as I always do— how they define success?

They simply hope that people recognise the thoughtfulness of their expressive activities while finding them attractive and meaningful. If others appreciate the value they have worked hard to create and communicate, that would be success.

I enjoyed the conversation with Shinpei & Michiko more than expected, ending with promises & invitations to visit each other in the future. It left me thinking about myself, my work and my interpretation of nature. How might I combine a sense of adventure with my creativity and perhaps experience the world more deeply through my own interface?

…and so it goes.

James Gibson

In a time where human actions are ever more interconnected and reciprocal, James —through travel, photography, film and creative writing— is exploring the topics of ‘design your life’, ‘do-nothing design‘ and ‘well-being’ from a viewpoint of natural regenerative design. The whole time asking the question: Do you know what good health —micro to macro— feels like?

Photographs courtesy of mikikurota architects – Copyright mikikurota architects 2021 or as stated.

Find mikikurota architects

Instagram: @mikikurota

Homepage: mikikurota.com

Homepage: Mountain Gear Project

Find James Gibson

Instagram: @bigson2000

Homepage: www.arukari.co

Sign up to his email newsletter here.