Jomon and Okhotsk Cultures at the East End of Japan

I had arrived in the Nemuro region of Hokkaido—having written this much, I can almost hear you say I’d reached the easternmost end of Japan. And you’re right, if you spread out only a map of Japan. Now try pointing at Nemuro on a globe. With Sakhalin island lying farther to the north and Chishima Retto, aka the Kuril Islands, stretching into the Sea of Okhotsk, you might see why I felt more as if I was standing at the gateway to the Northern Territories. Since several of my friends had recently migrated there, Nemuro came to feel much closer, and I took it as a chance to revisit the region around the end of the winter.

My mind was already set on making a tour of the lakes on the Nemuro Peninsula. And through my rounds, I learned that some of them are inland sea-lakes formed by sea-level rises from the Holocene glacial retreat. One such lake is Lake Tosamuporo, near the tip of the peninsula. The surrounding area is dotted with over a thousand hollows believed to be pits dating back to between the Early Jomon (about 7,500 years ago) and the Okhotsk culture (5th–13th centuries), offering evidence that the area was inhabited by humans since ancient times.

Although I travel to Hokkaido once a year, this trip to the Okhotsk coast made me appreciate anew the connection between humans and the sea, and that the primitive lifestyle of fishing, hunting, and gathering has slowly continued into the present. I suppose I owe my realization largely to Hokkaido’s unique history after the Jomon period. That is, even after mainland Honshu transitioned into an agricultural society in the Yayoi period (2,500–300 years ago), the life of fishing, hunting, and gathering was carried over to the Epi-Jomon period in Hokkaido (2,500–1,400 years ago). The inland sea-lakes may be covered with ice in the winter, but during the other seasons, they turn into large mudflats, becoming a habitat of shells and small critters, and attracting birds that feed on them. The coast is also a stopover for large migratory animals, which came to attract humans in search of game. The nature of Nemuro is the very picture of the food chain. Later, for lunch, sitting at a counter seat of the conveyor belt sushi restaurant Hanamaru (my must-go in Nemuro!) and feasting my eyes and palate on all the fresh fish I would never find in a sushi-go-round joint in Tokyo, I tried to imagine the depth of the time passing by. Perhaps even the food I was eating then and there hadn’t changed much from the food people ate thousands of years ago.

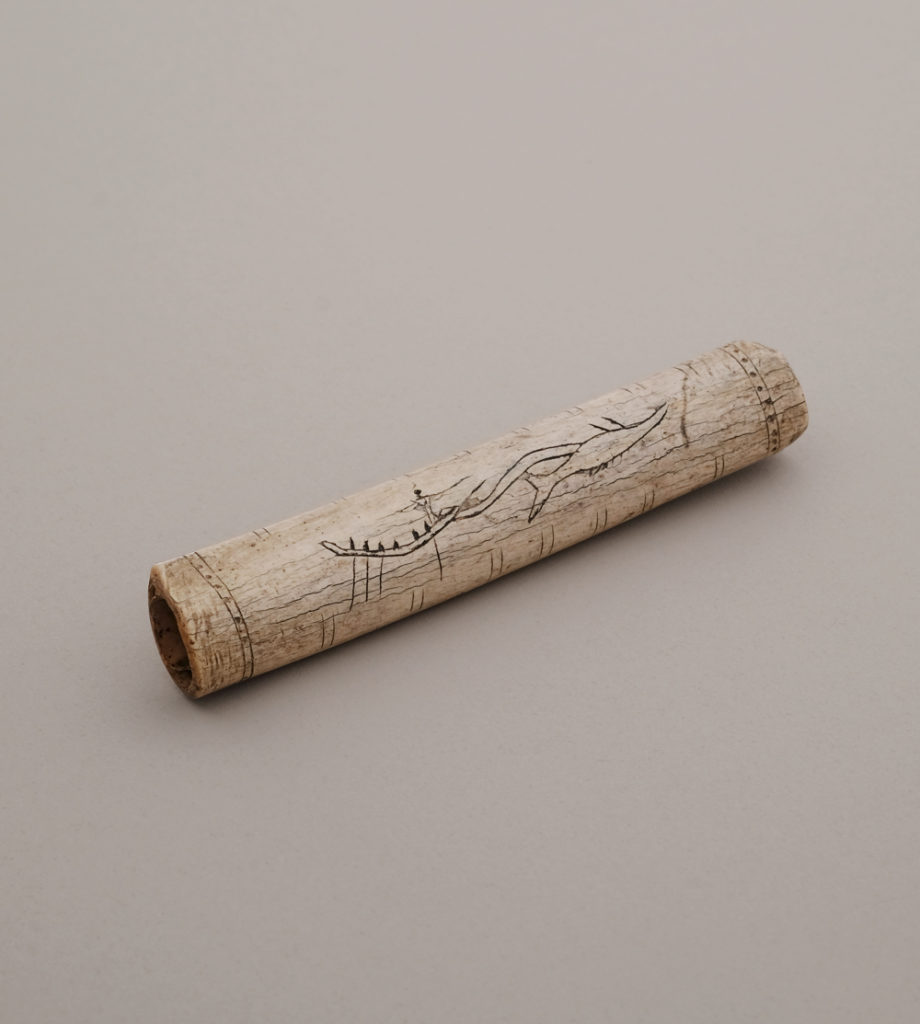

During this trip, I also visited the Nemuro City Museum of History and Nature. I had been there before to see dogu clay figurines dating back to the Late Jomon (4,400–3,200 years ago). This time, I wanted to see a relic that I only knew from pictures, namely, a needle case engraved with the image of a whaling scene (Okhotsk culture, Bentenjima site, ca. 6th–8th centuries). I had heard on the news a while ago that the discoverer donated his collection ahead of his hundredth birthday. With special permission from the museum, the needle case was brought out, and I couldn’t help admiring the petroglyph.

In it, a boat is rowing out to sea with a crew of seven. One of the men is standing with his arms wide open. He is holding a harpoon. Ahead of the boat is an enormous whale that looks like it has already been speared twice. Clearly, the image depicts the sense of tension immediately before a capture. I imagined that similar scenes unfolded throughout the Jomon and Epi-Jomon periods.

Apart from this case, the collection also included bone tools like fishhooks and other fishing tackle. Each item seemed to be imbued with the dignity of life, and I admired them one by one while wondering what their makers—the Okhotsk people—were like. Research in recent years suggests they were closely related to the Nivkh, an indigenous ethnic group of Sakhalin island, but I haven’t been able to study the population up close in person. I’m looking forward to the the day when I will be able to journey across the waters to Sakhalin.

< PAPERSKY no.56(2018)>

Jomon Fieldwork | Nao Tsuda × Lucas B.B. Interview

A conversation between ‘Jomon Fieldwork’ Photographer and writer Nao Tsuda and Papersky’s Editor-in-chief Lucas B.B. The two discuss the ways Jomon culture continues to play an important role in modern day Japan. The video was filmed at Papersky’s office in Shibuya in conjunction with Tsuda’s exhibition “Eyes of the Lake and Mother Mountain Plate” held at the Yatsugatake Museum in Nagano.

Nao Tsuda | Photographer

Through his world travels he has been pointing his lens both into the ancient past and towards the future to translate the story of people and their natural world.

tsudanao.com