To the outside eye, the practice of shodō (Japanese calligraphy) often appears as an ancient craft tradition, more an old-fashioned pursuit of retirees and hobbyists than a serious artistic practice. Yet shodō has a storied history as a contemporary art practice, through elevation by artists such as Isamu Noguchi and Yuichi Inoue. It is deceptively simple, yet contemplative. Still, yet kinetic and capable of unsettling the viewer.

While its popularity continues to ebb and flow, young champions such as Daichiro Shinjo are forging new ground for shodō – challenging its traditional form and finding new space at the intersection of writing, performance and storytelling.

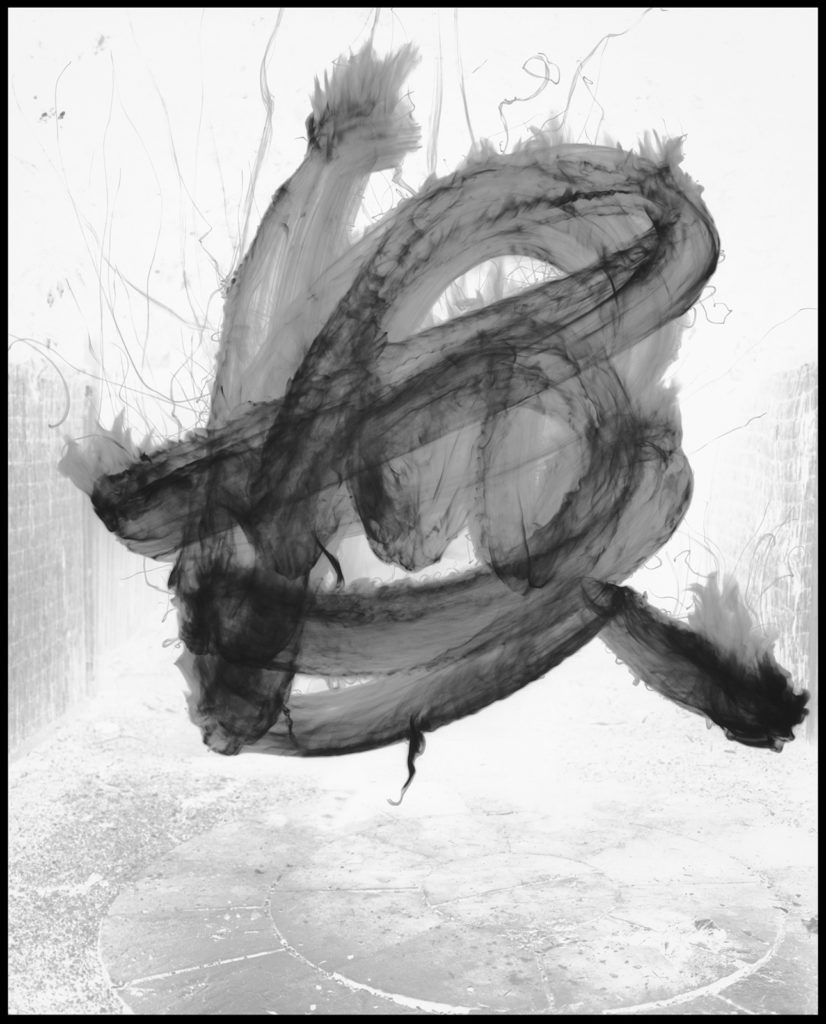

DARUMA, 2020, Sumi on canvas, 1950mm*1950mm

Your Grandfather (a revered zen monk and folklorist) had a big hand in your introduction to shodō. I’m interested in his approach.

Daichiro : My grandfather wrote commandments. But his instruction to me was not based on techniques. He ingrained within me the ability to ask questions and think spiritually. When asked to draw a circle, he would ask, “But is it really a circle?” Kind of like that.

Writing about shodō often feels weighted towards the meaning of the characters and preservation of tradition. Do you think this focus can be limiting to your practice?

Daichiro : Starting with an acceptance of the existence of words and letters, my expression is a “question” of those entities. Although words and letters have a common understanding, the emotions of the “present” in the body before being verbalized must be different for each person.

That is why I want to express the inside of myself that is not bound by the tradition and conventions of writing.

Do you have a particular wish as to how people engage with your work?

Daichiro : I hope that each person will feel free.

Once, an English friend of mine turned one of my works on its side and complimented me on it, saying he liked it better this way. That kind of reaction is interesting – because he didn’t understand the letters had no attachment or understanding to the letters I wrote. I see it as a form.

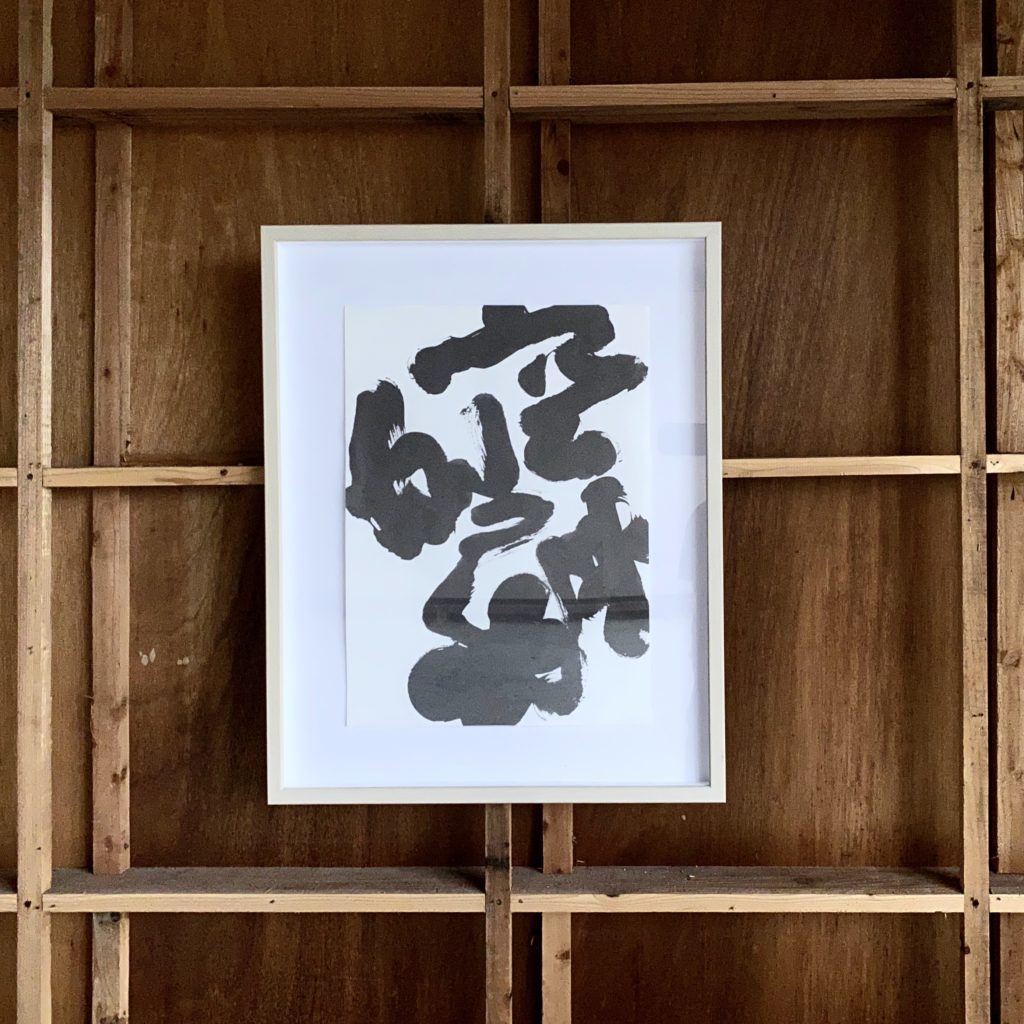

SORA(KU-), 2020, 420mm*594mm

Context seems to have a strong role creation of your work as well.

Daichiro : I don’t want to forget about the power of each landscape and the affection of the people I meet, but I forget these things as time passes. Even if I don’t exactly forget, the freshness of the memory will disappear.

I always bring a brush with me when I go to a land I don’t know. I feel like a photographer goes on a trip and takes a picture. Shodō feels close to photography for me.

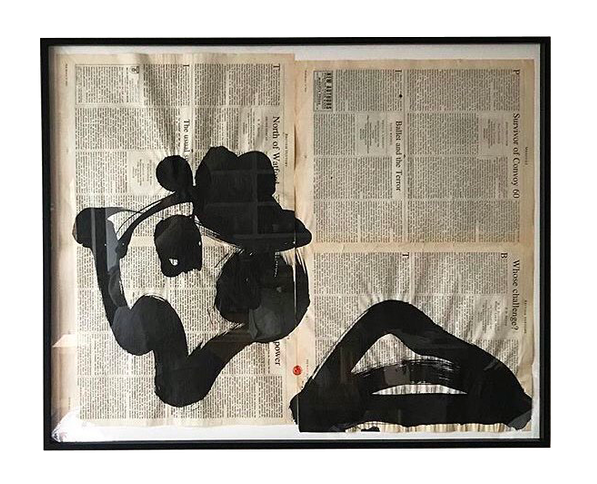

I will pick up an (unreadable) local newspaper from the area I visit, mix my ink with the local water, and write the words and shapes I feel on the balcony of the dormitory or hotel where I am staying.

How about the work you produce in your studio in Okinawa?

Daichiro : My atelier is located in Miyakojima.

As you can see from its history, Okinawa has been an island that has endured many dramatic changes – economic rationalism, scenery that changes brilliantly and unstoppable political pressure.

On the other hand, the root of human beings and the unchanging spirit can be seen in small ritual events in the village.

Because I grew up here, I wonder what the identity of this island is. I feel that such an environment leads to expressions that repeatedly ask questions of the reality, society and self.

Is that challenging in the social context of Japan?

Daichiro : Japan is known as a “safe country,” yet at the root of this I feel that there is an underlying sense of individual closed-mindedness. It is important to think about the balance of life, but there are too many senses that can be lost if we rely too heavily on organisational thinking.

Polite collaboration is a proud culture, but it is easy to lose yourself. You need to be aware that you are in control. Isn’t it important to believe in yourself first without being swept away by power and its surroundings?

Absolutely. You also spent some time living abroad in London. What impact did this time have on your practice?

Daichiro : The area I lived in was very exciting, as there were many unique shops and galleries. I also made a lot of artist friends.

Since it is a town with many immigrants, I feel that there was a good atmosphere where values were respected. However, on the other hand, it was also an area with a mixture of high-rise apartments and dilapidated walls covered in graffiti.

The reason why there are so many art scenes in the city also makes me think about the existence of political oppression. It was also the time to think about roots because I was a foreigner myself in this land.

What about yourself, do you have other non-artistic interests?

Daichro : Cooking!

It’s artistic too, I think! And lastly, What do you want to do in, say, a year’s time?

Daichiro : I would like to invite an overseas friend to Miyako and spend a few months working together. I’m preparing for that now.

Thanks Daichiro, all the best!