Story 01 | The rhizome inside us

The world has weaved baskets for over 10,000 years. It is the one craft which almost all ancient cultures share, but none of those old baskets are still with us. The soft materials they were made from – grasses, reeds, cane or bamboo – have perished, but traces of them remain, imprinted in clay and stone. To understand how basket weaving in Japan relates to that past, how it turned simple weaving into an art, and how these baskets may soon disappear, you need to travel to Beppu: the run-down hot spring resort town on the coast of Kyushu, in southern Japan. Here, the craft of traditional bamboo basket weaving has become an industry and an elaborate, but declining, art; the world today doesn’t seem to need weaved bamboo baskets.

“But, it’s always been very close to Japanese people, it’s been a part of their daily lives for a really long time,” says Ichiro Iwao, a 57 year old bamboo weaver. Behind him as he talks are hundreds upon hundreds of bamboo baskets that he has made. Every imaginable shape, weave and finish that a basket could have. They sit, unused. His raw materials come from a local supplier but in another 20 years he suspects he will have to go to the mountain and cut the bamboo himself, “the bamboo cutters are getting too old, so i’m studying this process myself.”

About 500 years ago bamboo baskets were a part of almost everyones daily life. Local farmers made these baskets for the cooking and preparation of food, sold to the community by traveling salesmen. Up on the second floor of Ichiro Iwao’s workshop, looking out across the modern city of Beppu, it’s hard to get a sense the old world which produced these baskets purely out of necessity. “My grandfather only began working with bamboo in 1920. Now i’ve been doing it for 30 years.”

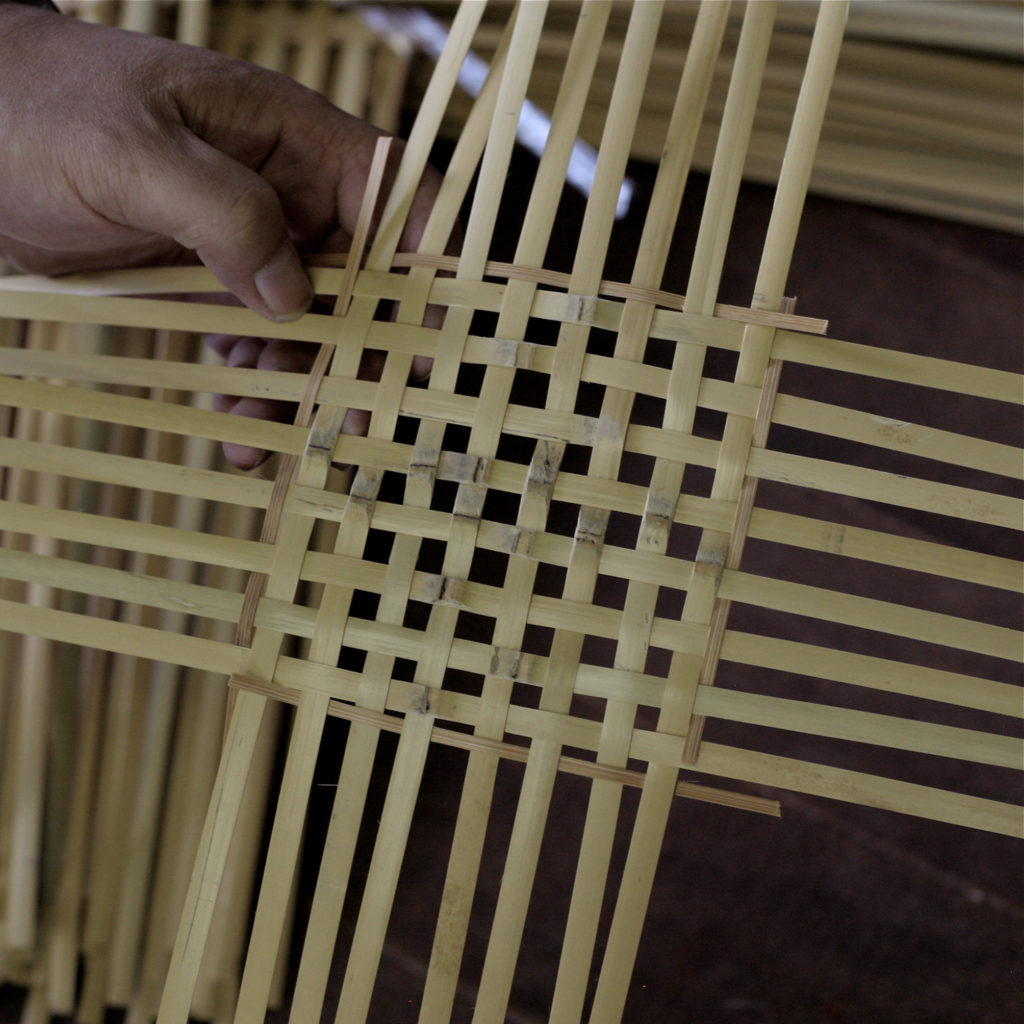

He stops to show us how he works, sitting cross legged on the floor, looking out across Beppu. He folds the bamboo carefully, weaving a complex base (the base determines the quality of the final product), before beginning the the curved sides. “I always wonder, why does this bowl need to be made out of bamboo, why is it important that it’s made from bamboo?” It’s the flexibility of the material and “its strength, which curves into beautiful forms.” But he feels there is something else about the material which makes it essential, something he struggles to articulate. “We had a closeness with bamboo in older times,” he says at the end of the interview, “but now we have grown far apart. When I talk about this with local children, I talk about how their history and the history of bamboo are connected, how bamboo is in their DNA.”

< PAPERSKY no.41(2013)>