Strolling a nature trail steeped in history

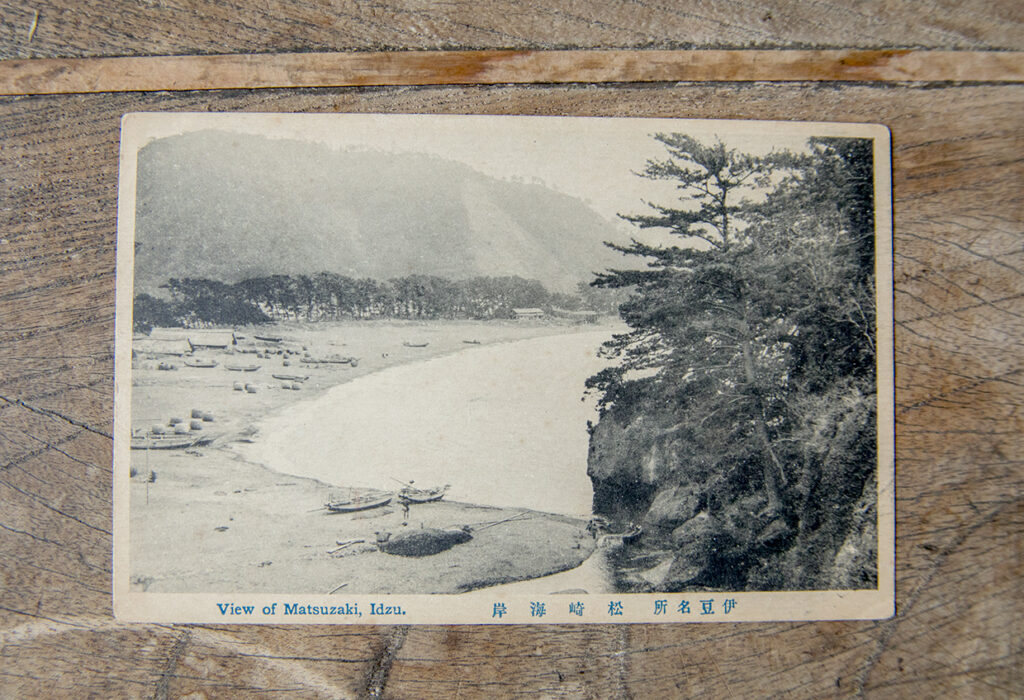

With its rugged coastline, boundless blue ocean and sunset on the horizon, Nishi-Izu is a place of exceptional beauty. Together with film director David Allen, Papersky visited the town of Matsuzaki in Shizuoka Prefecture, nestled in the low mountains of the Amagi mountain range. This charming little port town evokes a sense of adventure with its black and white namako walls.

A forgotten old trail has been groomed in the small mountains of this town. In this district, where charcoal production thrived from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period, there were seven highways and a network of minor roads connecting the highways to the villages. This track, named the “Yamabushi Trail,” was used to convey charcoal from the kilns built in the mountains down to the villages.

The road was revitalized by Junichiro Matsumoto, who explained its origins:”It was originally developed in the Heian period as a community road. The vicinity is also home to Hozoin, a sacred site founded by Kobo Daishi, and is thought to have been used as a path for ascetic practices by mountain priests.”

An elderly local man tipped him off about an old footpath leading to Amagi and Shuzenji, and he decided to explore the hills behind the temple just for the fun of it.。

“The old abandoned road we finally uncovered had not been used for more than half a century, buried under fallen trees and leaves. After the end of the war, when charcoal burning was discontinued, the road seems to have fallen into obscurity. Nevertheless, the original outline of the trail was preserved. There were traces of extensive maintenance during the Edo period using cut-throughs and other means to allow sleds and horses to traverse the area to transport charcoal.”

Ever since boyhood days, Matsumoto-san has loved being on the road, traveling, and walking.

While still at junior high school, he sojourned from his hometown of Yokohama to the Kii Peninsula hitchhiking by himself. At the age of 17, he traveled to Nepal alone to trek the Annapurna Circuit. He then journeyed to India, China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, hiking trails in the Himalayas and the Karakoram Range. What stirred Matsumoto, who is all too familiar with the dynamic charms of overseas trails, was the interesting ever-changing scenery of the low mountains and the stories that lie in the ancient trails.

“At first, I started maintenance work alone, lugging a hoe and chainsaw, but as I cleared away fallen leaves, earth, and fallen trees, I found a number of horse-headed Kannon and stone monuments. I also excavated Kan’ei Tsuho coins from the Edo era. Imagining how this road was used more than 200 years ago, I felt a sense of romance that I have never felt even in Tibet or the Himalayas.”

He then approached the local municipality, the owner of the mountain, and the chief of the village that owns the road, and launched a full-scale satoyama maintenance program called the “Nishi-Izu Ancient Road Restoration Project; that was five years ago. So far, Matsumoto has excavated and maintained seven routes, totaling 40 km of ancient trails. He uses these trails for guided mountain bike tours and also undertakes forest maintenance work for the Forestry Agency.

Together, we walked along one of the actual routes. First, we headed to a trail located on Mount Fukino at an elevation of 550 meters, which can be accessed directly from the coast. Although it was a low mountain traverse, points with good views afforded us with views of Nihondaira on the other side of Suruga Bay. On clear days in winter, you can even see as far as the Southern Alps, a view unique to the Izu area with the sea and mountains back to back. Along the way, there are the ruins of charcoal kilns, and a number of reminders of a bygone era of heavy foot traffic, such as the Horse-headed Kannon and Jizo statues dug out in the course of the trail’s maintenance. The path, which is shaped like a half-pipe, may be a remnant of the sledges used to transport firewood.

While it may have started as a trail-loving flight of fancy, the maintenance made it easier for hunters to enter the mountains, and some people even started growing shiitake mushrooms here. As such, the maintenance of trails contributes to the preservation of the mountains.

“When I am not guiding, I work on road restoration and forest maintenance, and the trees I cut down are sold locally as firewood. Sometimes the wood is used as fuel for wood stoves, and sometimes it is used to smoke Izu Tago-bushi (bonito flakes), which is a traditional practice in the neighboring town of Tago.”

In the past, the waters around Izu were rich in high-quality bonito, and the climate of western Izu was ideal for making bonito flakes; the area flourished as a major production center of bonito flakes and was seen as the eastern equivalent of Tosa and Satsuma in West Japan. In particular, once the Tago artisans established the process of making honkare-bushi (which involves a triple culturing mold process to enhance the flavor) Izu-bushi became known as a delicacy in its own right.

Firewood from various trees felled from the local mountains was indispensable for the production of Izu-bushi. Yasuhisa Serizawa of Kanesa Katsuobushi Shoten, which makes bonito flakes using the traditional hand roasting method inherited from Tago Town, explains: “In order to protect the fishing grounds for bonito, we needed to protect the marine ecosystem. And In order to protect the ocean, we had to maintain the mountains to prevent landslides and muddy waters.”

“Of course, the thicker trunks of the hardwoods produced a more fragrant, higher quality smoke when burned, but the craftsmen of the time must have known that the trees had to be cut for firewood in order to protect the mountains.”

He also provides wood to local woodworkers who have their own workshops and use it as a building material. The interior of Matsumoto’s office, renovated from an old storefront in the Matsuzaki-cho shopping district, is decorated with boards made from thinned hardwoods such as yamazakura and matebashi, which were harvested during maintenance.

“If we can confer the benefits to the trail and the people who work on it, the townspeople will recognize that this trail is a valuable asset to the community. In fact, as the abandoned path was transformed into a trail and people began to visit from Tokyo and the suburbs to see it, many media outlets began to visit to cover the story. This led to a better understanding of the local community, and prompted people to volunteer to help with maintenance.”

Matsumoto is also launching a new guided tour for walking on trails in the hope of “introducing old roads in their natural state, because I love paths steeped in history and pristine mountains.” While mountain biking tours are of course great, you can observe the sunset over the ocean from the trails, feel the sea breeze while you are in the mountains, and leisurely savor the unique climate and seasonal changes of Nishi-Izu. This trail lends itself perfectly to this kind of experience.

Because of the road, interactions are born, and from human interactions, culture is nurtured. Although it once fell into disrepair, 2 centuries later, a new culture is emerging that fits the modern way of life.

“Tracing the history and exploring the life of the people on foot is a quintessential Japanese style of travel. I think it is rare in the world to find a trail that blends the elements of a road with the elements of daily life and a nature trail,” added David. The history of the trail and the stories that emerge from it are truly inspiring to the modern pilgrim.