Story 03 | The making of giants souls

Takashi Kitamura lives in a typical suburban home on the outskirts of Aomori city. But his backyard is not typical, it’s a jumbled network of half-made wireframes, stacked one on top of another. Looking closer you might see a hand here, blending in with half a sword there, or is that a demons face? It’s a collection of works-in-progress (or a graveyard of half finished ideas) which have spilled out from his garage. Building a Nebuta is difficult, complicated work, it’s a job which begins almost as soon the last festival finishes.

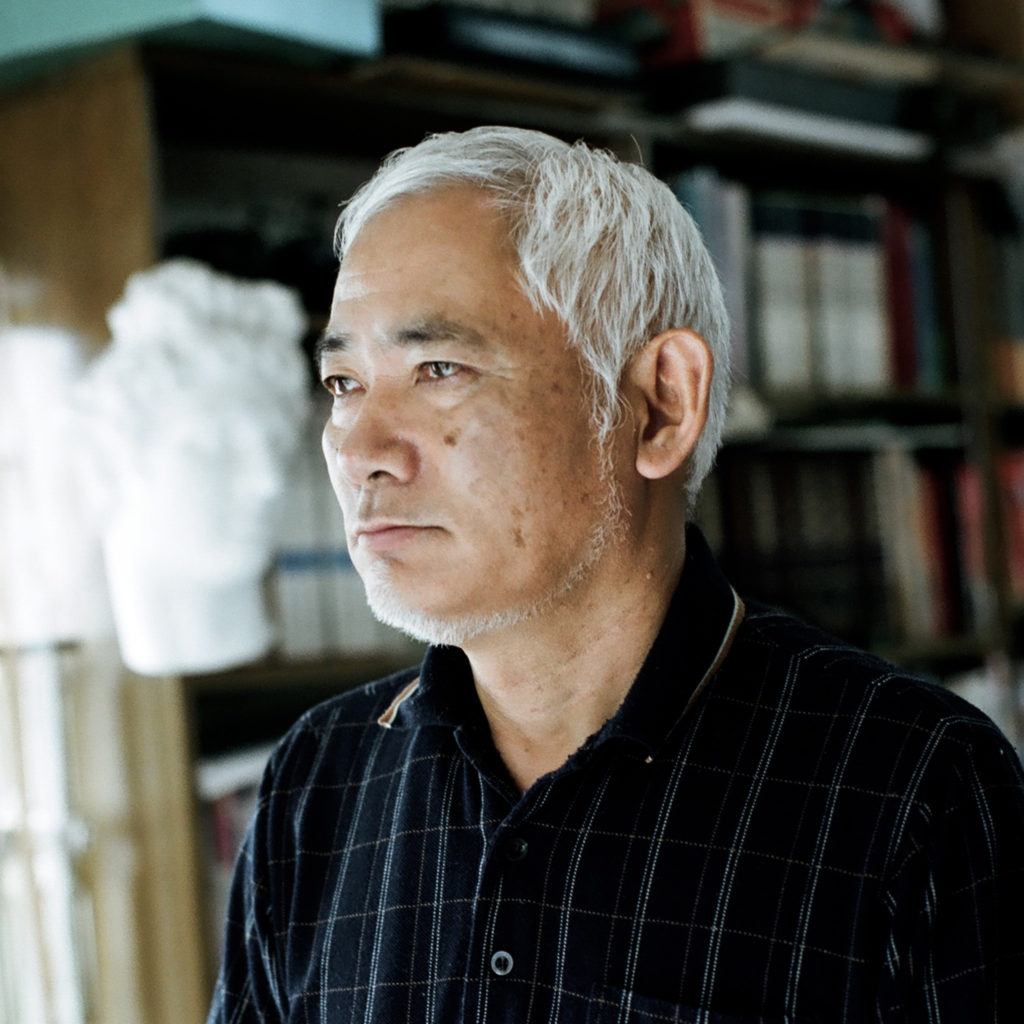

Kitamura was born in Aomori and began working as a professional Nebuta-shi when he was 30. “It’s a recent thing for Nebuta-shi to become professionals and work full-time,” he says, seated on a sofa in his living room. “There were only a few artists in the Showa times, now there are 12-13 artists who are professional Nebuta-shi.” Kitamura, who at 65 is the oldest Nebuta-shi in Aomori (and one of the few professional full-time artists), has made 90 Nebuta in his career. The production cost to make one Nebuta is approximately $200,000. There is no other traditional craft or festival in Japan with those kind of production costs. “Labour and electricity are the most expensive parts of the Nebuta,” he says, “and no one self funds, it’s impossible.”

As a tradition, the Nebuta festival is interesting because it is not connected with either Buddhism or Shinto, but with brands; corporate sponsors cover the production costs of each Nebuta. It’s a practice that began after the war to increase local tourism in Aomori, allowing Nebuta to become, in a way, the Formula One of traditional festivals; an expensive secular spectacle. To survive as a professional Nebuta-shi in this environment can mean making up to three Nebuta per year, as Kitamura often does. “The hard years for me are the years when I don’t have many sponsors. If I have a few sponsors, I can make different ideas and produce many sketches. Those are the best years.”

But his proudest year was 2012, when unexpectedly, for everyone in Aomori, Kitamura’s daughter also decided to become a Nebuta-shi and, with the help of a sponsor, became the first woman in the history of the festival to direct a Nebuta. But it shouldn’t be surprising, Nebuta history is all about change and adaptation. “I want to make the best Nebuta I can…traditional styled Nebuta,” she emphasizes, entering the room, still wearing her tool belt, “but at the same time I’m a woman and that makes me different. If I have children the way I work will have to change, my whole style will change.”

< PAPERSKY no.42(2013)>