Story 01 | Burnt by flames

12,000 years ago the world’s first forms of pottery were made in Japan. Archaeologists have retrieved fragments of this Jomon ware (cups, bowls and other items) all over Japan. Today, in the Imbe area of Okayama in Western Japan a form of pottery still exists which gives life to those dead fragments of clay. Known as Bizen-yaki (Imbe is part of an area formerly known as Bizen Province) it is the oldest living form of pottery in Japan; one of the six forms of pottery which were adapted from Korea’s stoneware tradition during the Heien period around 1200 years ago.

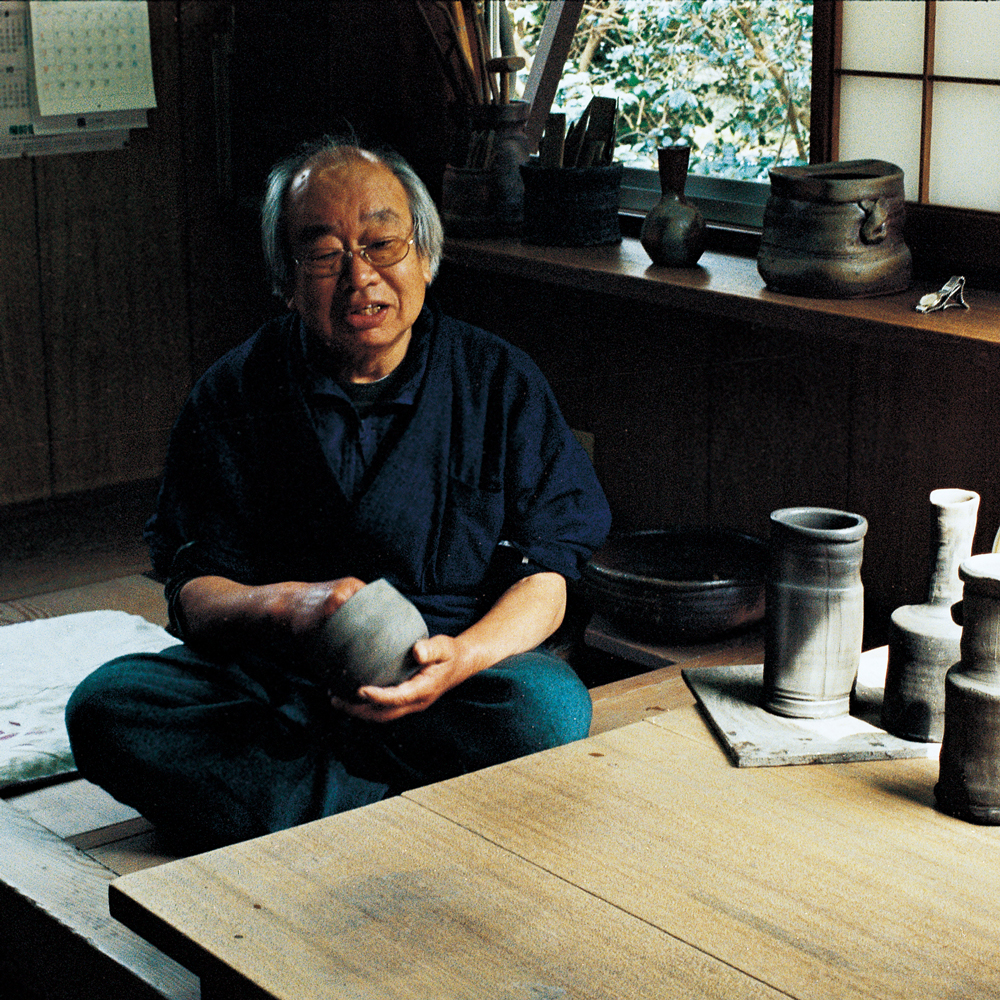

Eisuke Morimoto, a 52 year old master Bizen-yaki craftsman is sitting opposite us at his home in Imbe. He has white hair, dresses in sandals and a tunic and is extremely relaxed. His skittish white haired dog, Take, balances out the calm by barking as we talk. “Modern art is fashionable now, and that makes me want to return to more traditional forms,” he says. Morimoto’s teacher, Toyozo Arakawa, instilled a desire for traditionalism but stressed the importance of “making the old forms fit yourself and your style.”

Morimoto holds up a bowl. Deep red circles eclipse dark brown moons; a shining blue mark crosses over these shapes and travels up onto a silver lip and down into the dark charcoal interior. “My skill is the way I bring out the red color. It’s easy to get an uncooked red, but a cooked red is very hard to achieve.” We are taken over a bridge to a small bulding. Inside is Morimoto’s four chamber Nobori-kama (Nobori style kiln). It looks like a sprawling African mud hut. “The kiln determines what kind of pottery can be made. At first it was very hard to control, but after a few years it became much easier.” The 35 year old kiln is fired only once every year. Inside, uncooked pots, cups and bowls are stacked on top of one another, and separated with rice straw to ensure the vessels don’t fuse together. This stacking will determine the eventual markings and coloring which will cover the cooked clay surface. “The fire must be kept extremely hot. We will feed wood into the kiln 24 hours a day for 10 days, feeding the kiln in six hour shifts.”

To get the characterisitic Bizen-yaki effect, no glaze or paint is used. The colouring is created by qualities already in the clay, brought out under extreme and enduring heat during the firing process. “The best time was during the bubble, in the eighties, now is not a great time.” These days people are much more careful with their money, Morimoto is not so concerned though; “I think people who buy Bizen-yaki now value it more.” Morimoto’s desire is to have his work treasured, not as art, but as a part of their daily life, “When people use my work in their daily lives ― like drinking beer, eating pickles or rice ― that makes me happiest.”

< PAPERSKY no.35(2011)>