Story 03 | Circling Toward Nothingness

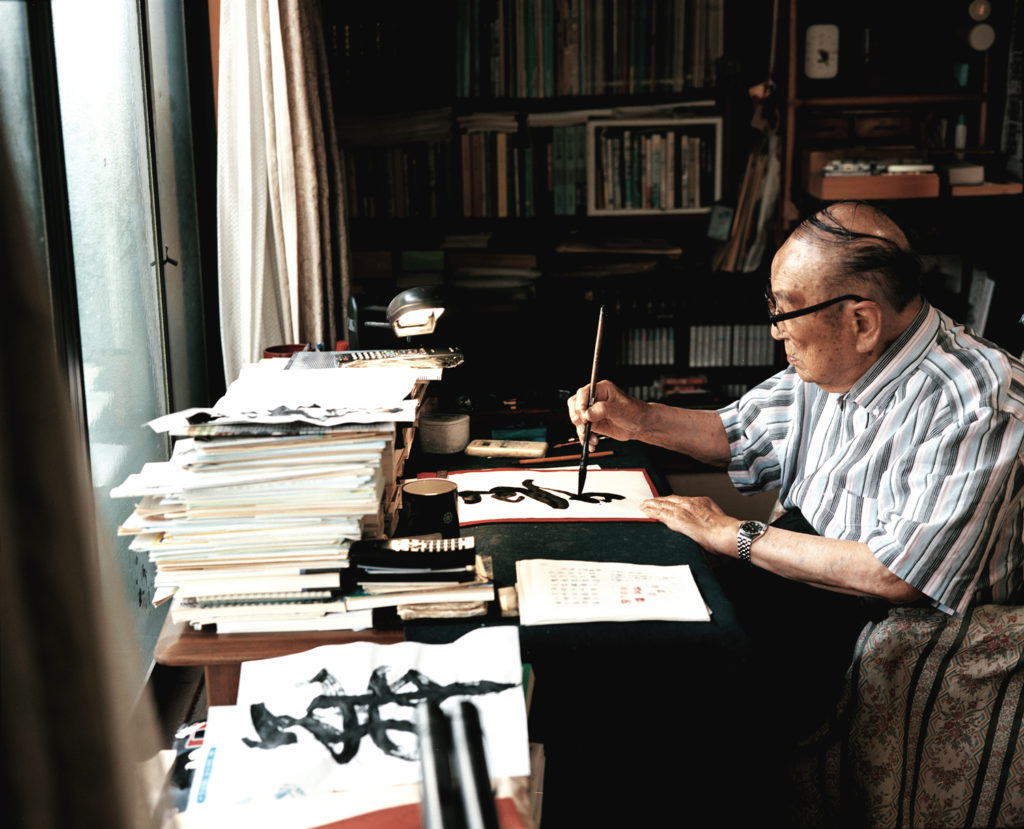

Thick and black; shining in the fading sunlight. A small sea of ink rests inside the pool of a carved Amehata stone Suzuri. This sumi ink, made from bamboo ash mixed with melted fish bones (and dried into a solid stick) has been ground by Taiun Mochizuki, a 95 year old shod (calligraphy) master. On the floor of his room long white sheets of paper have been marked in thick brushstrokes with words, poems, songs and sayings. What words are his favorite? “I have many favorite words” he laughs, and begins searching at length through his documents, finally discovering an A3-sized page with a long numbered list. Taiun Mochizuki is a revered man in Yamanashi, for both his Shodo ability and teaching.

He tells us that Shodo culture can ― like many of Japan’s traditions ― have its roots traced back to India. Here tortoise shells, wood and bones were inscribed with pictographs seen in artefacts dated as early as 200BC. That tradition of inscribing then spread from China, where writing culture flourished dramatically and where inkstones were first developed. Writing culture then travelled further East to Korea and finally, to Japan, where it was modified to meet local needs. Over the journey the technical side of writing was simplified down to four tools, the “treasures of the study” as they were called in China: paper, ink, brush and inkstone (Suzuri). But today, of those four, Suzuri is the most threatened. “Shodo culture will not die anytime soon, it is taught in all Japanese schools. I used to teach it in the forties and fifties,” says Taiun Mochizuki. “But Suzuri making, that is really threatened, especially the Suzuri from Amehata.”

These days the local monkey population far outnumbers people in Amehata but it wasn’t always so wild and forgotten; “there used to be almost 10,000 people living in the mountains near Amehata Village when I was twenty-one. I remember we used to bathe in the river in those days.” That was the era when he first began taking Shodo seriously, but his earliest exposure to the form of writing came when his father would call him and his siblings together to show them beautiful written letters. “He’d say ‘you should write like this,’ I remember that well. I was the oldest of nine siblings, now I’m the only one left.” Taiun Mochizuki is very old, and as we lose track of our talk about Shodo and Suzuri he talks easily about events and memories from vastly different eras and continents. Many things change in a life lived so long; some things remain constant. Every time he writes, dipping his brush into a small sea of ink resting in a carved Amehata stone, he tries to invoke the same meditative state, calling upon those memories from the past.

“I put all my life into my Shodo, I put everything in. My whole life goes into what I am writing. All my experiences come together in one small moment and it feels like nothingness. And that all starts with the Suzuri, it’s just my movements and the stone. No thinking.”

< PAPERSKY no.36(2011)>