For all the years of preparation and investment, the Paralympic and Olympic games last a few short weeks each. Despite their fleeting existence, the infrastructure, energy and resources expended to host such large scale events can shape the experience and structure of a city for many decades – as was the case with the 1964 Summer Olympic Games in Tokyo.

This time around, with much of that infrastructure already in place, the city is set to host a Games that aims to honour the legacy of 1964 through the re-use of a number of key venues. The following cycling course re-visits five of the important landmarks from 1964 beginning in Setagaya:

Komazawa Olympic Park (Gymnasium and Stadium)

One of the few remaining venues from the 1964 games to miss out on a second coming at the 2021 Olympics, the complex that previously hosted the Wrestling, Football, Volleyball and Field Hockey sadly won’t be utilised for competition this time around.

Constructed in 1958 to the design of architect Yoshinobu Ashihara, the large sporting complex sits on the site of a former golf-course (where Emperor Hirohito once shared a round with British monarch King George V) and includes several dedicated facilities. While taking a few warm up laps around the popular, leafy cycle-course you can observe the pagoda-like control tower and striking curved roof of the subterranean gymnasium.

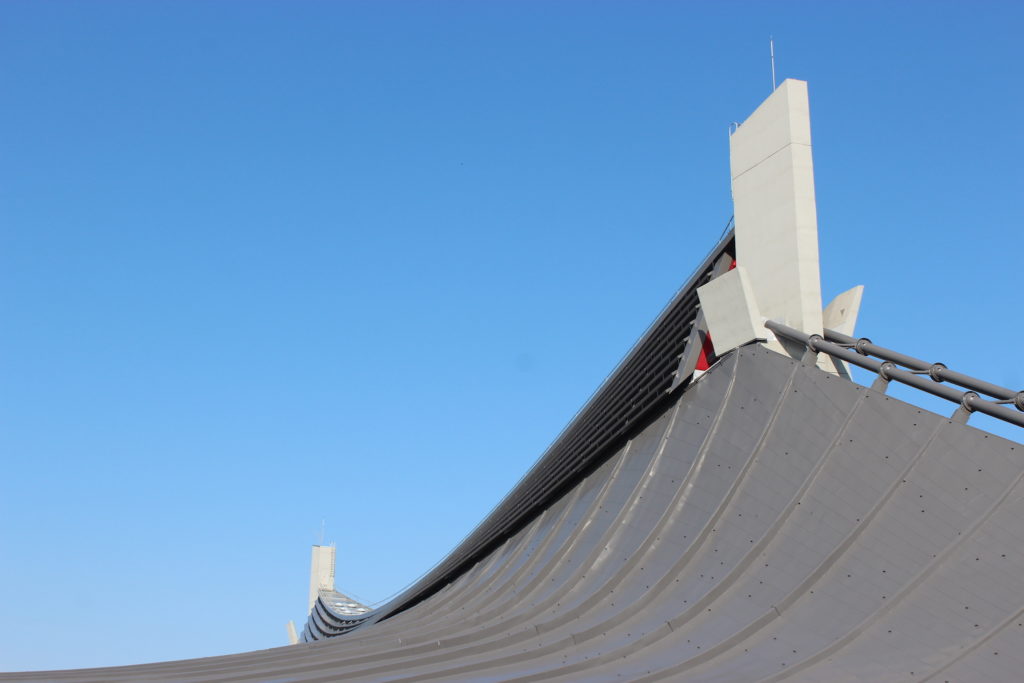

Yoyogi National Gymnasium

A relatively straight-shot from Setagaya, at the Southern end of Yoyogi Park sits the Yoyogi National Gymansium. Formerly the site of swimming, diving and basketball during the ‘64 Games, this time around the space will be home to handball, wheelchair rugby, and badminton.

Designed for the 1964 games by acclaimed architect Kenzo Tange, the sweeping, sculptural form of the catenary roof provided a welcome architectural expression to the kinds of technical innovations that earnt the Games the title “The Science Fiction Olympics.” Seen as an attempt to integrate a Japanese sensibility with developing engineering technology, it remains a hugely influential work of modernist architecture.

Japan National Stadium

A short cycle through the metropolitan greenery of Sendagaya to Meiji Jingu’s Outer Garden connects the Yoyogi complex to the new, utilitarian Japan National Stadium. The steel $1.6 billion stadium sits on the site of the former 57,000 seat National Stadium (itself a re-incarnation of the 1930 Meiji Jingu Gaien Stadium).

It was his schoolboy experience of using the swimming facilities at Tange’s Yoyogi Gymnasium that its architect, Kengo Kuma, credits for his decision to become an architect. The 60,000 seat stadium that will host the Track and Field, as well as the Opening and Closing Ceremonies was completed in 2020 following the highly controversial scrapping of a previous design by the Late British architect Zaha Hadid.

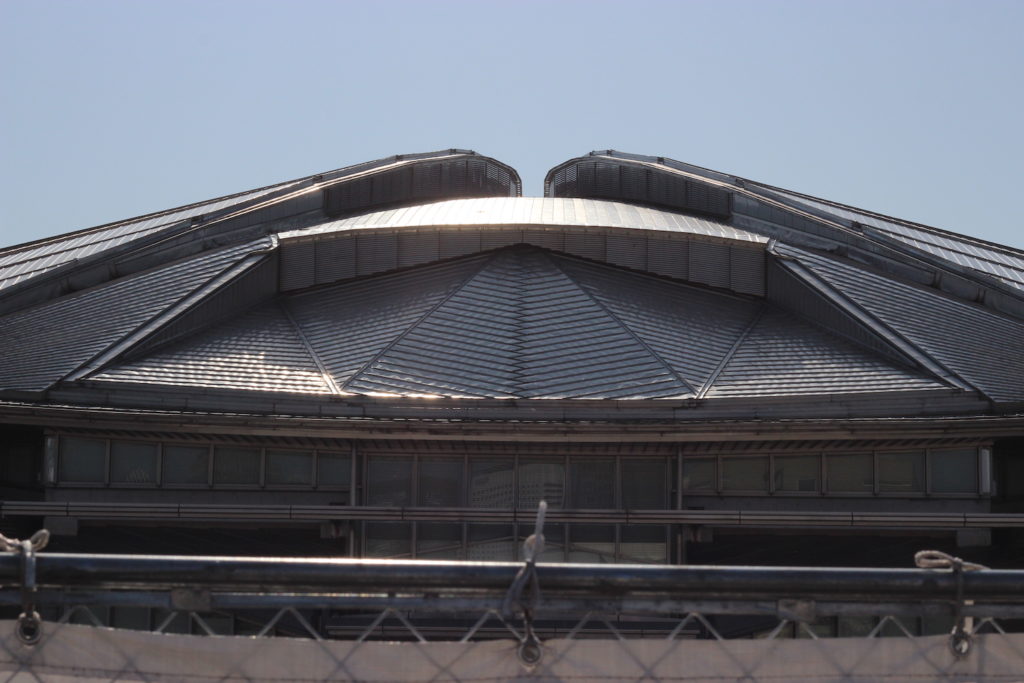

Metropolitan Gymnasium

Adjacent Sendagaya station (and directly opposite the new stadium), you can cycle around the much loved Metropolitan Gymnasium. Originally designed to host the 1954 World Wrestling Champs, the building held the waterpolo and gymnastics in the 38th Olympiad, and will host table tennis this time around.

The glittering, beetle-like roof was re-designed by Pritzker prize winning architect Fumihiko Maki in the late 1980s. It has a capacity of 10,000 spectators and regularly hosts events and concerts outside of Olympic duties.

Nippon Budokan

Looping around the Meiji Jingu Outer Garden complex and continuing alongside the Akasaka Imperial residence towards the north end of the Imperial Palace, the octagonal Nippon Budokan in Kitanomaru Park marks the final destination of the ride.

Designed by Mamoru Yamada as a Martial Arts hall to accommodate Judo at the 1964 Olympics, the distinctive building has hosted numerous concerts by famous musical artists (beginning with its opening rock concert by the Beatles in 1966, against the protestation of purists who felt Western pop would defile the Arena). Karate and Judo again will take place at the venue in 2021.

Leveraging an existing infrastructure, the re-use of key, well-connected venues in the center of the city builds on the legacy of the 1964 games in an attempt to project a more sustainable future. Although it can be difficult to see inside these publicly funded stadia, a leisurely ride on two-wheels is a great way to understand some of the impact of the 1964 Olympics on the Japanese Capital.