The calligrapher Kasetsu has presented innumerable Hana (Flowers) in a solo exhibition in her birthplace of Kyoto. Her compositions were showcased alongside those of her childhood idol Yuichi Inoue.

“In my heart, I know Kyoto is comfortable and cozy. I absorbed a great deal of the Kyoto spirit while I grew up there. But Kyoto is also a compact place, for better or worse, and showing my work there after a long gap made me a little nervous too.”

The exhibition “100 Hana: Calligraphy by Kasetsu” was organized in the summer of 2022, after an interval that was longer than the artist could remember. The idea was conceived by Taiichi Takahashi, the director of Gallery Kyoto Teramachi Nanohana, dedicated to collecting and displaying the works of, among others, calligrapher Yuichi Inoue (1916–1985) and ceramist Taizo Kuroda (1946–2021).

Though Kasetsu has worked with Mr. Takahashi for some 15 or 16 years, this was the first time he suggested juxtaposing her work and that of Yuichi Inoue. Neither is Kasetsu sure where Mr. Takahashi got the idea, nor did she bother to ask. In answer to her bewilderment, Mr. Takahashi only murmured What a showdown!

It isn’t hard to imagine how flattered Kasetsu was to show her work with that of her early influencer. And to her surprise, the works placed side by side created a calm, peaceful scenery. Rather than demand that the viewer compare the two artists, the countless Hana (Flowers) appeared to be free, comfortable, and in bloom.

“I expected the extent of Yuichi Inoue’s influence on me to be more obvious, but the juxtaposition actually highlighted the differences. For me, that was a pleasant surprise.”

Kasetsu observes a certain rule when setting out to produce a composition. In her words, she must choose her character with sincerity, for that character must be a “necessity of the moment.”

“Many people think composition begins with the selection of a character, but actually, that’s part of the very last stage. Before all else, I focus on the events that unfold from day to day, and in the corner of my mind, I try to come up with a character that relates to them and sums them up. When a potential character emerges, I consult the kanji dictionary and study it through and through. If it doesn’t feel right after all, then I let it go and start over. In this way, I take my time and zoom in on a single character.”

Kasetsu uses the expression nichi-nichi for “day to day.” In life, there are days when her heart feels happy and carefree, and days when her mind feels heavy and burdened. Rather than breaking down individual events or delving into her emotions, however, Kasetsu takes a step back and maintains a bird’s-eye view of her nichi-nichi. By doing so, she arrived at a character that she has continued to write every day for the past 12 years.

“In lieu of keeping a diary, I write the character nichi (day) every day. I was proud of myself for finding this character. I had been searching for a word that cuts right to the heart of daily life, and I felt like I found it at last.”

Kasetsu doesn’t enforce a strict routine on herself though. She has taken extended breaks, and then resume writing again, all the while adhering to just one rule: Never throw away a character. This rule is etched deep in her heart.

Kasetsu moved to Tokyo at the age of 30. Before that, when she still lived in Kyoto, every few years she sorted through her past work and disposed of it in bulk. Mountains of compositions on traditional Japanese writing paper, ordinary Western paper, and other miscellaneous sheets and scraps of paper—she loaded her car, drove to a waste treatment site that reminded her of a bottomless ravine, and dumped stack after stack by hand.

“At the time, I wondered what exactly I was tossing out. Perhaps I was discarding parts of me that I didn’t want to see. Perhaps I was editing my life.”

Again and again, old friends warned her against parting with her work. Kasetsu herself occasionally regretted letting go of her compositions. On reflection, she believes she might be doing just the opposite today in her daily routine of writing nichi.

“I’m probably trying to get back what I’ve lost. Or self-disciplining. Or, most likely, reflecting on and taking a fresh look at my stance on calligraphy.”

Kasetsu entered the world of calligraphy at the age of seven. Her teacher was Ms. Kumiko Tamaki, whom she respects and admires like a mother even now. Ms. Tamaki told the young Kasetsu over and over that it’s important to write the word beyond the shape of the character. Why did she choose a certain character? Why is she writing it? Just because was never a satisfactory answer. She was given as much time as it took for the word to ripen. Ms. Tamaki was kind and soft-spoken, but her gentle words also accentuated the firmness and rigor of her teaching. There was neither a way back nor a way forward. Kasetsu had to carve her own path, and the only way to do that was to find the right word.

“Come to think of it, in a way, I’ve been doing the exact same thing ever since. All along, I’ve continued to ask myself why I’m writing a certain character at any given moment. Through this, I’m afraid I also formed the habit of avoiding ideas for which I have no words.”

This may have been precisely the reason she threw her work into that bottomless ravine years ago. Those were spontaneous words that wouldn’t have had a place in her heart for very long. The necessity of the characters was weak, faint.

Select and discard—this process also overlaps with a portrait of Yuichi Inoue that Kasetsu saw as a child. The photographer Kazumi Kurigami captured Inoue sporting a shaven head and a casual short-sleeved kimono, carrying a huge jumble of paper under his arm and walking away, with his back to the camera, toward the fire in which he is about to incinerate his work. The ferocious photograph, as some might describe it, filled Kasetsu with awe. She hadn’t even reached the tender age of ten.

“At the time, I thought what I felt was a mixture of curiosity and fear. But in hindsight, I believe it was the dread of making a selection. I recognized the cruelty of selecting. After all, selection is an exercise of the ego.”

Around the time she discovered this portrait, Kasetsu was already producing her own “works,” and thus engaging in the practice of selecting and discarding. A calligrapher doesn’t simply write a character once and call it a day. It isn’t as easy as that. The process of composition includes selecting the best piece out of multiple tries.

Spreading out her sheets of writing across the entire floor, surveying the pieces from atop a chair, and selecting the best work—Kasetsu understood that this step was analogous to screening six months’ worth of her existence. Six months’ worth of writings, after all, were a sort of avatar of herself.

“Even now, selecting might be the idea that I have the most difficulty putting into words. If that’s so, then it just might be the most faithful mirror of myself.”

Kasetsu admits that some nuances are difficult to describe in words. She also says, quietly but with conviction, that the point of finding words is to clarify such subtleties. “However indescribable an idea may be, it makes me uncomfortable if I don’t even try to see its contours.”

One thing about Inoue that she did not imitate was his style of writing. Inoue worked with an enormous, heavy brush, and dragged it across the paper to form dynamic strokes. Kasetsu took into account her muscular strength and the length of her reach, and opted for her current style of writing with her entire body.

After 40 years in the business, however, Kasetsu is finding that her established ways aren’t working as before. She never imagined her body and spirit were separable, she says, smiling quietly. She has come to a crossroads where she must reassess her style.

“I dismissed the idea of dragging and hauling a heavy brush like Inoue. It wasn’t for me before. But I’m opening up to it now. After practicing for so long, I feel I need to embrace change in order to keep on going. Lately I think a lot about what it means to continue.”

Whatever the answer may be, Kasetsu says she wants to stay true to herself.

“Anyone can pretend to be anything today. But for those who care, I want to demonstrate that there’s a way to explore the essence. I care. I want to explore the essence—of people, of myself, of everything.”

The choices that Kasetsu has made to date are a mirror her life. They are flexible and will change over the course of time. In my mind, I revisit her process of creation up to this point.

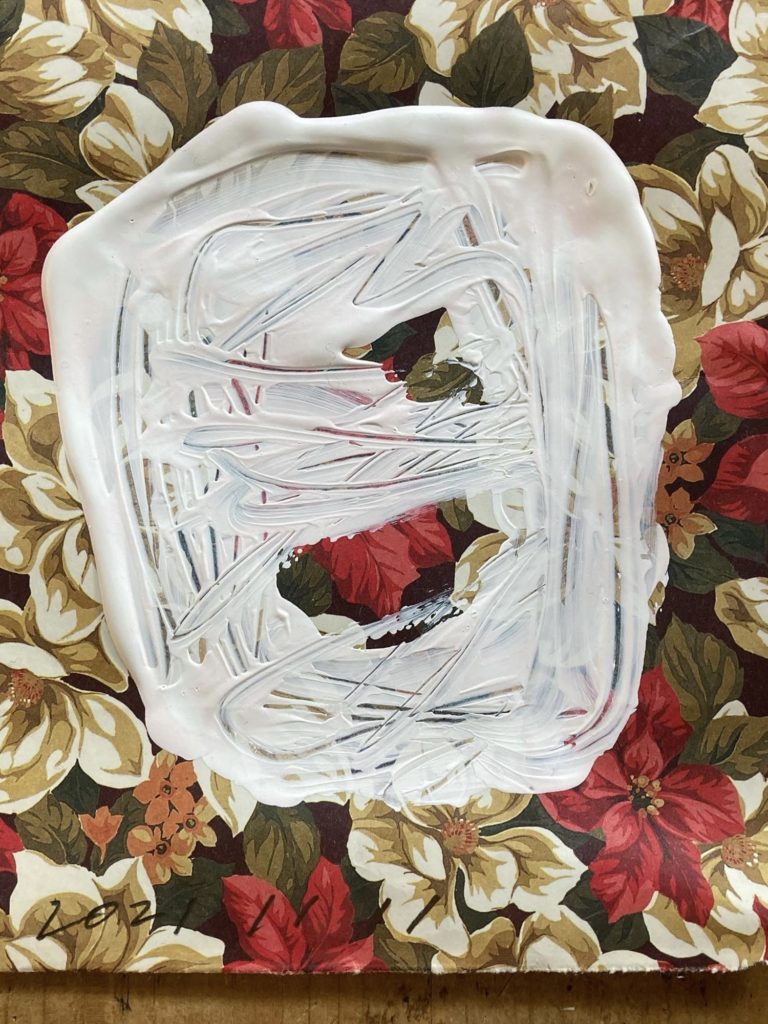

She beats the brush and strikes her limbs forcefully on the paper, and expels her breath and rasps and grunts. Thus completing her composition, she pauses, sitting still in a daze, her shoulders heaving. Her tension rubs off on me, the spectator, and I hold my breath too…

I am left trying to decode the message being delivered by this former student of psychology. I will keep waiting, as always, looking forward to her next word.

Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum 20th Anniversary Exhibition

Dates: Now on until December 25

Location: Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum

https://www.clematis-no-oka.co.jp/vangi-museum/exhibitions/1355

Kasetsu

Kasetsu was born in 1975 in Kyoto Prefecture. Her childhood discovery of kanji dictionaries compiled by the scholar of classical Chinese literature Shizuka Shirakawa (1910–2006) sparked her interest in the origins and definitions of kanji characters. She carries out her own diligent research into the roots of characters and works to express their intersection with contemporary events in single-character calligraphy. She also conducts workshops in, and outside Japan themed around exploring the possibilities of expression with kanji characters.