A Silk Farmer’s Quest for Jomon

This dogu clay figurine appeared to depict a lovely little girl. It seemed to be an intact, unbroken head and neck figure, although it might have been made to match with a separate body. The back of the head, curled like an animal’s tail, may have been the rendering of a twisted bun hairdo. The relic was tiny enough to fit in the palm of my hand, and it was elaborately made with a great deal of care.

The Fujiimachi area of Nirasaki City, Yamanashi Prefecture, commands a sweeping view of the Yatsugatake Mountains to the north, Mt. Fuji to the south, and the Southern Alps to the west. Here, I stood in a small earthen storehouse serving as a private archaeological museum called Sakai Kokokan, showcasing artifacts mainly from the Early Jomon (7,500–5,500 years ago) to the Middle Jomon (5,500–4,400 years ago) and up to the Yayoi period (2,500–300 years ago). The display cases were lined with dogu, clay bells, pottery with human face decorations, and phallic stone rods. Large objects like clay pots and metates were placed on the shelves and the floor.

In the early Taisho period, around the mid 1910s, fragments of obsidian were found in the neighborhood fields. This fascinated Takizo Shimura, a grade schooler at the time, and inspired him to conduct his own excavation work for over 50 years thereafter. The museum houses his collection of finds. Through the entrance is a portrait of Takizo’s mentor, the anthropologist and archaeologist Ryuzo Torii. A photograph of Takizo himself sits modestly to the bottom right. On this day, I asked his grandson Yasunori to give me a guided tour.

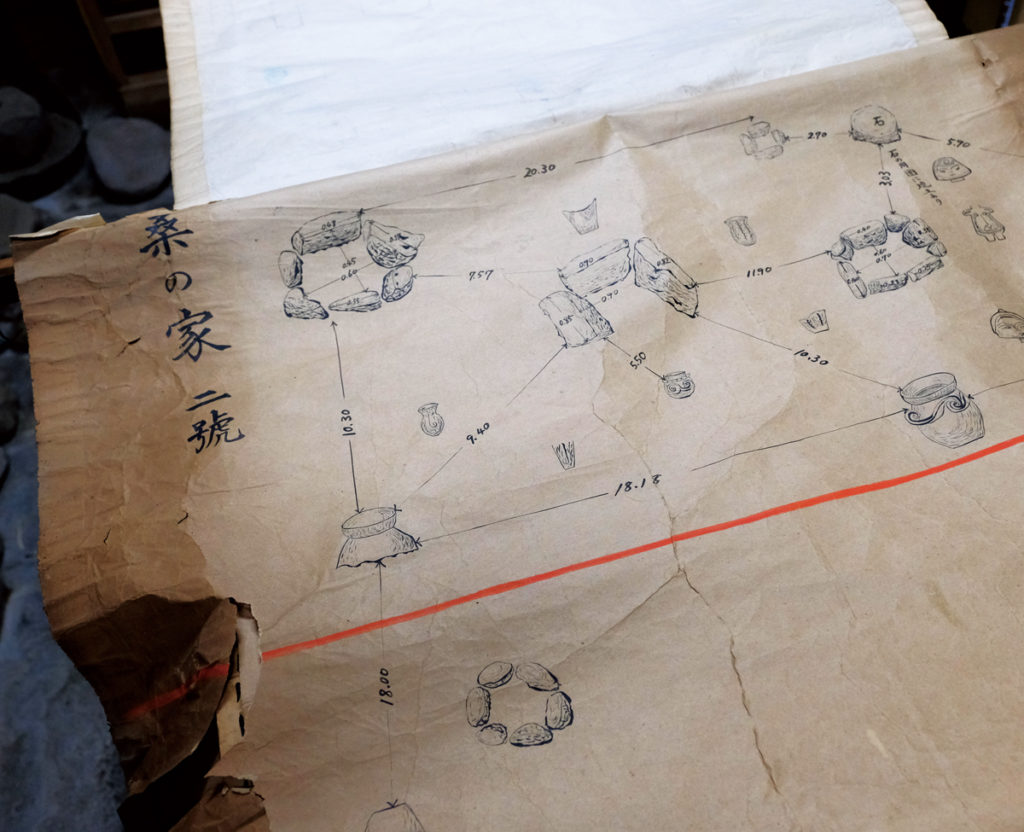

That the collection contributed pieces to the British Museum’s exhibition “Power of Dogu,” spoke of the significance of Takizo’s unearthed finds. For the visitors to his storehouse, Takizo also prepared booklets with his comments on the artifacts, complete with hand-drawn sketches and diagrams, and strove to spark the viewer’s imagination.

Getting to that point, however, was no smooth sailing. Takizo’s family ran a silk farm, meaning the excavation work was carried out on the side. Because spring and summer was the busy season of farm work, the only time dedicated to digging was autumn and winter. Takizo took great pains to present his work in a self-published excavation report.

His journal includes records of optimistic days: “March 31, 1950. Cloudy. After two straight days of being held up by the rain, each of us was itching to get to work. The location of the peripheral walls being unclear, we hatched a plan to remove the topsoil to find the floor and thence seek the walls, and started digging. As we approached the floor, we quested after the black earth mixed with wood ash, and at last reached the floor. . . . The discovery of human-faced stones, vessel stands, and carbonized lengths of timber became a source of strength for us and gave a new lease on life to the excavation itself.”

And then there were sluggish days: “Feb. 4, 1954. Cloudy. The temperature rose above −10ºC, but the ground is still covered with 30 centimeters of snow. My eldest son, Tomizo, and I cautiously made our way through the snow to the site. . . . At 3 p.m., the northern winds turned violent and robbed our fingers and toes of the freedom to move. After warming ourselves by a small fire, we mustered up the courage to concentrate our efforts on the northern trench. Alas, we still could not find the peripheral wall before the of our day.”

Life is a succession of challenge after challenge—this much may be true, but the grandson Yasunori adds affectionately that his family’s challenges could not have been overcome without the support of the women.

Perhaps things were the same for the Jomon people: The diligent, hard-working men relied on the soothing presence of the women to live fulfilling lives. “Life” might also refer to the view that unfolds when we seek to overcome a succession of challenge after challenge. I took a fresh look at the dogu figurine, and its expression seemed like a symbol of the matrix.

As the evening approached, I went to the top of a gentle slope that was once home to a mulberry field, where a dwelling site was preserved today. Beyond the remains of a furnace into which the Jomon residents fed their fuel wood, there stood a stone rod, completing a welcome space awaiting someone’s return.

<PAPERSKY no.55(2017)>

Jomon Fieldwork | Nao Tsuda × Lucas B.B. Interview

A conversation between ‘Jomon Fieldwork’ Photographer and writer Nao Tsuda and Papersky’s Editor-in-chief Lucas B.B. The two discuss the ways Jomon culture continues to play an important role in modern day Japan. The video was filmed at Papersky’s office in Shibuya in conjunction with Tsuda’s exhibition “Eyes of the Lake and Mother Mountain Plate” held at the Yatsugatake Museum in Nagano.

Nao Tsuda | Photographer

Through his world travels he has been pointing his lens both into the ancient past and towards the future to translate the story of people and their natural world.

tsudanao.com